By Peter M. Sanderson, 20 August 2025

2016

Being resource rich but revenue poor, the government of Nunavut and the Kitikmeot Inuit Association (KIA), proposed a “nation building project” – a 900 km all-season road over the permafrost to access the resource-rich areas of Nunavut, terminating at the future deep sea port of Grays Bay. The first 400 km have already been built by three NWT diamond mines, and when the last mine closes in 2026, it reverts to a public road.

2018

The government of Nunavut and KIA made a presentation to the Senate, see the coloured GBRP map, attachment one. Note the large number of mine sites that would bring jobs, prosperity to the Inuit and revenue to the Nunavut government.

When it was obvious that southern Canada was not ready to invest in Inuit prosperity, the government of Nunavut dropped out of the project, leaving KIA to carry on.

2023

Legally the KIA leads the project, by creating and then owning the West Kitikmeot Resources Corp (WKR).

2024

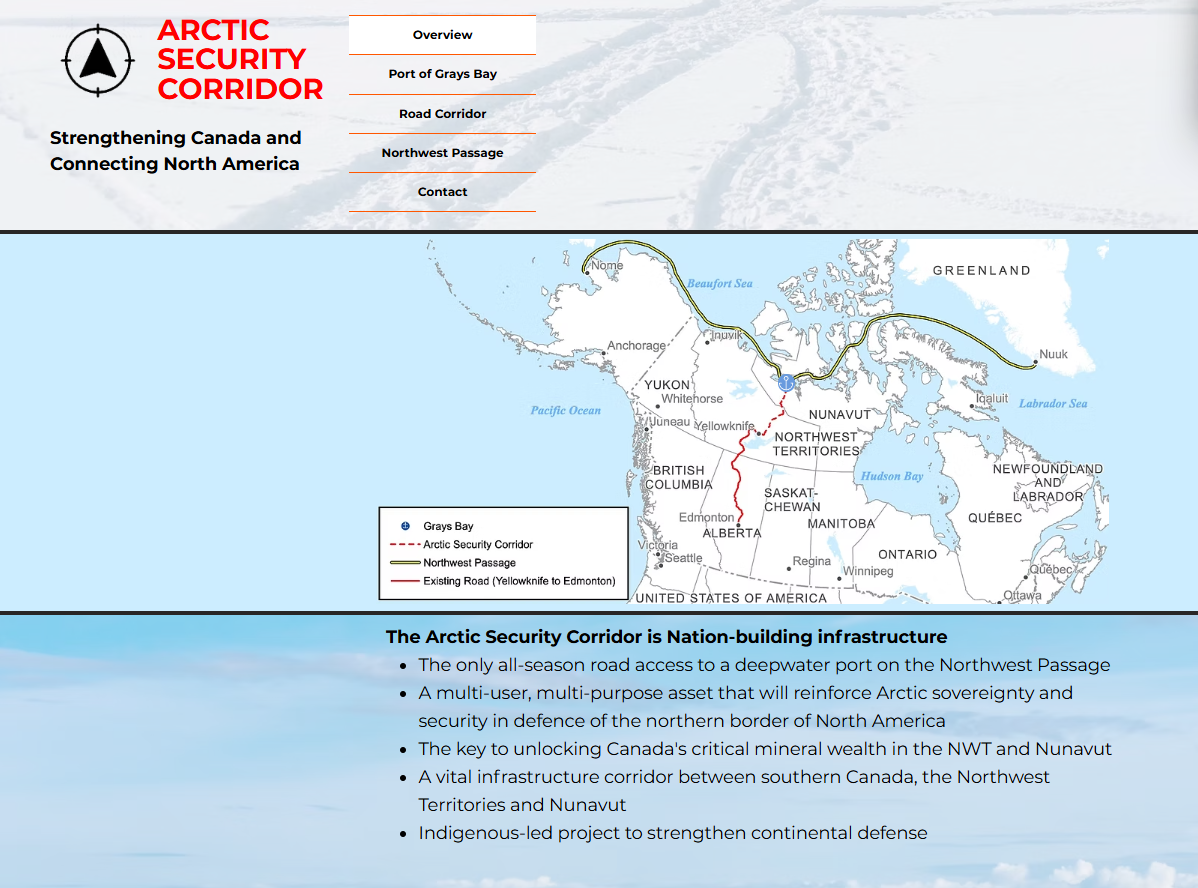

WKR reads the room and in February re-markets their road and port project as the Arctic Security Corridor, see attachment two.

NATO expects Canada’s contribution to be the defence of its Northern Arctic flank. Suddenly southern Canada finds that it needs an Arctic coast fueling station – a tank farm at Grays Bay – fed by tanker trucks traveling up the all-seasons road from Yellowknife, NWT. The Canada Infrastructure Bank shows up and signs on to the project that September.

2025

At the June 3rd Canada’s Premiers Meeting, Prime Minister Carney called out the Nunavut’s Grays Bay Road and Port as a “nation building project,” a real example of a “consensus project” that he wants to move ahead quickly.

Nothing is Done for the Right Reasons

Inuit householders don’t care that it’s a NATO/civil duel-use project, they are finally going to get year round, weekly, inexpensive, fresh, truck delivered food – plus jobs and their turn at prosperity.

Image: a screenshot from the Arctic Security Corridor homepage. Credit: West Kitikmeot Resources Corp, provided via author.

9 thoughts on “The Amazing Evolution of the Grays Bay Road and Port Project”

The Grays Bay Road and Port project is being packaged as ‘nation-building’ and ‘consensus politics.’ On the surface, it promises prosperity: cheaper food for Nunavut, new jobs and a much-needed fuel hub for Arctic operations. But the strategic picture is far darker than the sales pitch.

Look at the mines clustered along this corridor. Many are tied, directly or indirectly, to Chinese state-backed firms. Beijing isn’t interested in Inuit prosperity, it’s interested in securing critical minerals to feed its industrial and military base. By investing public money in this ‘Arctic Security Corridor,’ Ottawa may actually be subsidizing Chinese access to Canada’s resource heartland.

And infrastructure is never neutral. The same all-season road that can bring lettuce to Kugluktuk can also bring armour south. Picture it not as a supply road but as a spear shaft:

Day 1: A heavy-lift vessel docks at Grays Bay, unloading armour and mechanized infantry. Within 24 hours, an advance guard is rolling south along the all-season road.

Day 2: A brigade combat team, a couple of hundred tanks and APCs is making 250 km of progress a day across terrain that normally acts as Canada’s natural shield. The wilderness ceases to be a barrier; the road has turned it into an open lane.

Day 3: Forces reach the Mackenzie corridor, threatening Yellowknife. With the airfield and road junctions under pressure, Canada’s interior lines fracture.

Day 5: Armour pours into northern Alberta. The oil sands and refineries are suddenly within reach, while Ottawa is still debating whether to call it an ‘incident’ or an ‘invasion.’

That is the military logic of roads and ports: once built, they don’t just move groceries; they move divisions.

At the June 3rd Canada’s Premiers’ Meeting, Prime Minister Carney called out Nunavut’s Grays Bay Road and Port as a ‘nation building project,’ a real example of a ‘consensus project’ that he wants to move ahead quickly. Of course, in Ottawa, ‘consensus’ usually means everyone agrees to spend money while quietly disagreeing on who benefits and Beijing is more than happy to scoop up the change that falls between the cracks.

If Canada truly intends Grays Bay to be a ‘security corridor,’ then security must come first:

No Chinese control of mines tied to the corridor otherwise we’re paving Beijing’s supply chain.

Dual-use readiness the port and road must be hardened with surveillance, air/maritime ISR and denial capacity, not left as open infrastructure waiting to be exploited.

Strategic sovereignty planning integrating this corridor into broader defence posture, including Arctic patrols, NORAD modernization, and NATO interoperability.

Without those measures, Grays Bay risks becoming less a symbol of sovereignty and more a vulnerability, one that adversaries could exploit with trucks, with ships, or with tanks.

Oh, come on.

Very few Canadian mines have any significant Chinese ownership; an article I read recently on critical minerals suggested there was only one.

The Chinese couldn’t get to Grays Bay without sending a large fleet into the heart of Canadian territory, something no one would mistake for anything but an invasion.

Roads are narrow corridors vulnerable to attack from the air and they go both ways; if Chinese tanks are rolling south, Canadian tanks can be rolling north and meet them at a place of our choosing.

Only the Canadian side would have air support.

The Chinese could land at any West Coast location – say Prince Rupert – in far greater numbers and with less warning; and could cut off such a location from ground-based reinforcements by blowing up a couple of highways and a single rail link.

China isn’t interested in a land invasion of North America any more than we are interested in a land invasion of China; their objective is to control trade and coerce foreign states through the threat of force, not occupy them (the principal exception is Taiwan, which they do intend to annex). This may require them to defeat the US navy and air force, which is why they have embarked on a vast military buildup, and is also why Canada, a US ally, may be forced to fight them.

There is no additional strategic risk from building the Grays Bay road.

Michael, no one’s planning for “PLA tank brigades down a Nunavut gravel road.” A land invasion is obviously Hollywood. The real risk is leverage: Beijing’s near-Arctic state playbook plus dual-use infrastructure plus resource offtake control. That’s how they shifted the balance in the South China Sea incrementally, not with an invasion.

Receipts (Canada & near-North): it’s not “only one.”

• Nunavik Nickel (Deception Bay, QC): Canadian Royalties was taken over by Jilin Jien (China) — that’s who built the operation out. Operating mine, Arctic port access at Deception Bay.

• Wolverine (Yukon): Yukon Zinc was bought by Jinduicheng Moly/Northwest Nonferrous (China). The mine later collapsed into receivership; Yukon is now carrying environmental risk, useful reminder about control vs. liabilities.

• Selwyn/Howard’s Pass (YK/NWT): Selwyn Chihong (subsidiary of Yunnan Chihong Zinc & Germanium) holds this world-scale Zn-Pb project. That’s Chinese state-linked capital in a strategic corridor.

• Izok–High Lake (NU): Proponent is MMG—major shareholder: China Minmetals. Their own materials detail the Izok/High Lake plan; and the Grays Bay Road & Port (GBRP) is the enabling corridor on the books with NIRB.

• Rare earths policy fight (NWT): When Vital Metals (Nechalacho) moved to sell concentrate to Shenghe (China), Ottawa helped pivot the stockpile to the Saskatchewan Research Council instead because supply-chain dependence matters.

This pattern isn’t just Canadian: Greenland revoked a Chinese firm’s Isua iron-ore license, and also banned high-uranium mining — blunting a China-adjacent REE push at Kvanefjeld. Arctic governments are getting choosy for a reason.

“If tanks roll south, ours roll north.” Sure, but the real contest is below war: who sets the terms for access, shipping windows, and offtake when prices spike? That’s where roads and ports become bargaining chips.

South China Sea lesson learned: China didn’t announce conquest; it built outposts, runways, radars and missile sites on “harmless” reefs — and turned them into power-projection hubs. The method, incremental, dual-use, fait accompli is the cautionary tale for Arctic corridors.

So is there “no additional strategic risk” from GBRP? Come on. It’s a good nation-building project but it does change the board by hard-wiring export logistics for deposits whose proponents include a Chinese state backed major. That’s a manageable risk if we design for it.

Build it but with brakes: practical, low-drama mitigations

• Access control & visibility: ISPS-compliant port ops, permit-based dispatch, AIS/telematics on heavies, Indigenous guardian programs.

• Chokepoints by design: a few single-lane bridges, constrained causeways and pre-engineered barriers so Ottawa can lawfully restrict movement in a crisis without cutting off community resupply.

• Contracts & control: screen port operators and long-term offtake so effective control doesn’t drift to state-directed entities.

• Policy alignment: This is exactly why Ottawa tightened the Investment Canada Act rules and forced Chinese divestitures in critical minerals: to keep strategic levers at home.

Bottom line: No one’s fear-mongering an amphibious landing at Prince Rupert. The real game is influence, access and logistics. China has declared Arctic ambitions; it has a proven incremental playbook; and Canada has already started to firewall critical minerals. Build GBRP for prosperity — just don’t build it naïvely.

Sorry Michael, from the Canadian side, don’t you mean “the Tank”

Good afternoon Ted,

You make a valuable point that will require analysis and recommendations by the CAF as the government’s military advisor.

However, your imaginary scenario is not at all realistic, unless the Canadian government dithers catatonically as you suggest.

A more likely unfolding is that the road South is blocked at an appropriate point by rapidly deployed military units, initially probably the parachute companies of the army’s three regular infantry regiments, and then the invading column – and in particular its logistics trains – is smashed by Canadian (and probably American) airpower. The greater risk is more likely that, once they are in Canada, how to get rid of the Americans.

Ubique,

Les

Les, we agree the “tank column to Edmonton” bit is movie stuff. That was never the point. The risk isn’t a cartoon invasion; it’s leverage via infrastructure and logistics. That’s why I argued to build the Grays Bay corridor with deliberate control/denial features baked in up front.

On your tactical sketch:

1) “We’ll just drop the para companies and block the road.”

Canada does retain a limited parachute capability spread across the regular infantry, but mass airdrops in the Arctic aren’t turnkey. You need suitable drop zones, permissive winds/visibility, and a sustainment plan for light troops operating far from roads and medevac. Our airlifters can land on gravel, yes but staging, weather, and distance make “rapid” less rapid north of 65°N. (C-17/CC-177 and C-130J facts; gravel runways at Resolute, Cambridge Bay, Kugluktuk; and the post-Airborne-Regiment para construct.)

2) “Only the Canadian side would have air support.”

Air support isn’t a light switch. Fighters forward-deploy to NORAD FOLs (Inuvik, Yellowknife, Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet), but persistence depends on tankers and airborne early warning. Canada’s CC-330 MRTT fleet is still being converted (first fully-converted tanker deliveries from 2027), and Canada is only now moving to acquire AEW&C; in the near term, that means heavy reliance on US/NORAD enablers. So no, it’s not “only Canadian airpower.” It’s binational by design.

3) “The bigger risk is getting rid of the Americans once they’re here.”

That’s a bumper sticker, not policy. NORAD is a binational command under a treaty renewed in perpetuity in 2006; operations on Canadian territory remain under Canadian sovereignty and law. Domestic military assistance is also governed by the National Defence Act/Emergencies Act—not by vibes.

4) Why ‘build-with-brakes’ still matters even if we can fight:

The smarter (and cheaper) move is left of bang, design a few deliberate chokepoints, access controls, and lawful-disable features into the GBRP. That gives Ottawa options before anyone forces a crisis where you’re gambling on weather, airbridge capacity, and perfect warning. It’s exactly the lesson from China’s gray-zone playbook in the South China Sea: they win with incremental logistics and dual-use infrastructure, not tank rushes. Don’t be the guy who says the road changes nothing, especially when MMG (China Minmetals-linked) itself called Grays Bay a “game changer” for Izok–High Lake.

Yes, CAF can plan to block and smash given time, weather and binational enablers. But it’s better strategy to shape the terrain now so we don’t have to prove it later. Build the road for prosperity just don’t build it naïvely.

Good afternoon Ted,

We could easily have an endless discussion about the tactics to be used (or not) in the mythical scenario. However, there is no value in that, as I fully support your conclusion.

With regard to getting rid of the Americans after they come in, that has been a Canadian concern since right after World War II. It is now extremely relevant given Trump’s wish to destroy Canada and make it the Great Northern Territory (or a similar name) without any Electoral College power.

Ubique,

Les

Hi Ted. Keeping in the spirit of your “scenario” and Michael’s observations, let me contribute to the solution. The Chinese vanguard will be mounted on over snow tracked vehicles c/w AA missile units, so the Air Force may not be able to take out the road – US HIMARS will come up later. Route denial is the job of the Combat Engrs/Assault Pioneers but they won’t be able to get close. Road cratering would be a perfect NON-LETHAL role for the local Canadian Ranger Patrol. Using a camouflet set takes an hour to learn and basic demolitions skill can be learned in a morning. Once you destroy the 1.5 m of gravel roadbed and expose the permafrost – if it’s melting season, think Passchendaele with slush – make it so PLA runs out of bridging.

Don’t forget Lupin, 20 miles south with a 65-hundred foot runway, a suitable airbase for an air force.