Procrustes, 05 July 2020.

There has been a longstanding debate in Canada about the extra costs (i.e., the ‘domestic premium’) for building warships in Canada. Certainly the best exponent of the view that this premium is minimal and that comparing Canadian prices with the ship prices of foreign suppliers is misleading, can be found in the writings of Eric Lerhe.[1]

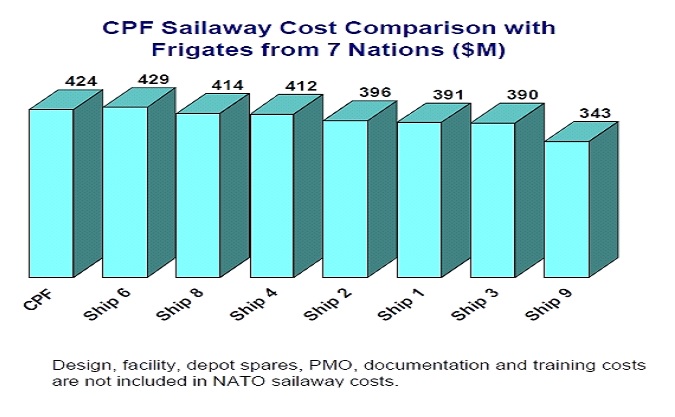

Using the Canadian Patrol Frigate (CPF) as his main example, Lerhe argues that a fair ‘apples to apples’ comparison of Canadian and foreign warship costs should include only the ‘sail-away’ costs of ships in accordance with the standard NATO definition. He uses the following data compiled by an internal DND report.[2]

Lerhe then divides the sail-away cost of the last CPF built ($424 million) by the average of sail-away costs of the remaining seven comparable ships ($396 million) to arrive at a modest 7% domestic premium for building in Canada.

Lerhe argues that we should exclude the program expenses Canadian shipbuilders incur (e.g., infrastructure additions/upgrades, design, development, project management, documentation and training, etc.) when calculating foreign ship cost comparison figures. But does this logically follow? The full cost of the CPF program to Canada was $9.310 billion.[3] This represents the real total cost to Canadians for building all 12 CPFs in Canada. Divide 12 into this total program cost and we get a per ship cost of $776 million. Divide this by the average cost of the ship comparison group ($396 million) and suddenly the true domestic premium jumps to 96%.

My point is that should Ottawa decide to procure warships abroad, it would only have to pay these extra program costs if we are poor negotiators! The real cost to Canada for buying warships abroad would be the price we negotiate, not those we incur via our own inefficient procurement system. Plus, if we are the first foreign customer, we might get many of these development costs waived as we did for the CF-18 fighter contract.

Therefore, from a buyer’s standpoint the sail-away price will be the starting point in contract negotiations; from a seller’s perspective, total program price per ship will be the starting point. If the buyer (Ottawa) is well prepared, all the seller’s R&D costs, cost overruns, development mistakes, shipbuilder subsidies, and so on, will be well known and can be quickly dismissed from the contract negotiations.

Those items which Lerhe and others try to leave out of the domestic premium because other states do not include them in their shipbuilding costs, add up to precisely the extra cost of doing business in Canada. This includes: the real cost of our dysfunctional defence procurement system; the delays; the inefficiencies; the higher than average profit rates we provide for our shipbuilders; and so on. We did have to pay for these costs on the CPF which Canada built domestically, whereas we would not necessarily have to pay for the same costs if we purchased future warships abroad.

The issue is not about relative labour or material costs, but rather all of the ponderous baggage that accompanies Canadian defence procurement. True, some of this would be present even if Ottawa procured warships abroad, but when Ottawa buys from domestic shipyards the weight of this baggage multiplies significantly. From shipbuilding delays to the politically driven demands for more and more ‘Canadian content,’ Canada spends a great deal more to build and buy at home. Without a contract been finalized, the price tag for Canada’s Canadian Surface Combatants (CSC) will soon exceed $5 billion per ship. For that amount, Ottawa could likely procure almost two, far more capable, Arleigh Burke destroyers, or about three of the USN’s currently planned FFG(X) frigates which should possess roughly the same capabilities as the CSC.

Here is a disruptive thought: let Ottawa buy 30 or more of the new FFG(X) frigates, insist on maintaining them in Canadian shipyards, and give a $1 million compensation payment to each of the roughly 4,000 Canadian shipbuilders. That latter cost would still put Canada and the navy ahead of where we are likely to be under the current National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS) build-at-home approach.

Numbers matter more to a country with Canada’s huge oceans backyard than does quality. Why do our main naval coalition partners need a few Canadian warships to chip into area air defence or even ballistic missile defence anyway? The days of some kind of ‘diplomatic return’ on naval contributions are probably long gone, and the current CSC variant Ottawa is procuring will not be able to keep up with a 30+ knot USN carrier battle group in any case. These warships are simply a vanity project for our navy – keeping up with the Big Boys. Of course, if Canada should actually opt for a 30-plus ship major surface combatant force [4], then the Department of National Defence would have to divert funds from both the air force and the army to recruit, train and field the personnel required by a much larger RCN. Not an easy prospect to be sure.

Our Big Three Canadian shipyards would protest loud and long to any such shift in shipbuilding direction. But they are highly unlikely to be viable concerns at the end of the current NSS building phase. Ottawa would not then be faced with the vibrant, self-sustaining, internationally competitive shipbuilding sector it was hoping for in launching the NSS. Instead, the shipbuilders will be lining up begging for make-work projects and outright financial bail-outs to keep them going.

Which path do you think the Canadian taxpayer would prefer? Buying affordable warships offshore when required, or investing continually in a Potemkin fleet to line the pockets of our shipbuilders and to allow our navy to preen occasionally in coalition operations? Wrapping a $5 billion warship around relatively few missile cells is not what Canada needs for its day-to-day anti-smuggling, drug interdiction, fishery and counter-piracy patrols, or even routine NATO missions.

NSS supporters will complain that there are bona fide reasons of security of supply, balance-of-payments, and industrial strategy, etc., for building warships in Canada. All this is true, but let us openly debate the real costs of following this path, and then leave it up to Canadians to render a judgement on the government of the day at the polls. They may decide that it truly is too expensive to build modern warships at home.

References

- For the best example of his views, see Eric Lerhe, “Fleet-Replacement and the ‘Build-at-Home’ Premium: Is It Too Expensive to Build Warships in Canada?” Vimy Paper No. 32 (Ottawa, ON: Conference of Defence Associations Institute, July 2016).

- Canada, DND, Chief of Review Services, “Report on Canadian Patrol Frigate Cost and Capability Comparison” (7050-11-11 CRS, 26 March 1999), p. 10.

- Canada, DND/PWGSC, “Interdepartmental Review of the Canadian Patrol Frigate Program, Report on the Contract Management Framework,” 26 March 1999, p. 5.

- A 30-ship fleet of surface combatants was the optimal number the navy proposed when the CPF ship program was under consideration by cabinet in December 1977.