Mikaël Perron, 30 March 2021

The National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS) aims at recapitalizing the fleets of the Coast Guard and Navy but also to rebuild and sustain our shipbuilding industry. The NSS now relies on two fully modernized shipyards that have started delivering ships under the program and a third one soon to tackle the overload of work (mainly the heavy icebreakers and ferries). Delays meant the strategy was initiated late and both fleets are in a dire need of recapitalization. The skills to build ships will also be necessary to maintain and refit the vessels throughout their service life because if we were to purchase ships from a foreign state, we might lose the capability to conduct major refits on them. We now realize how much it cost to let our shipbuilding capability whither away.

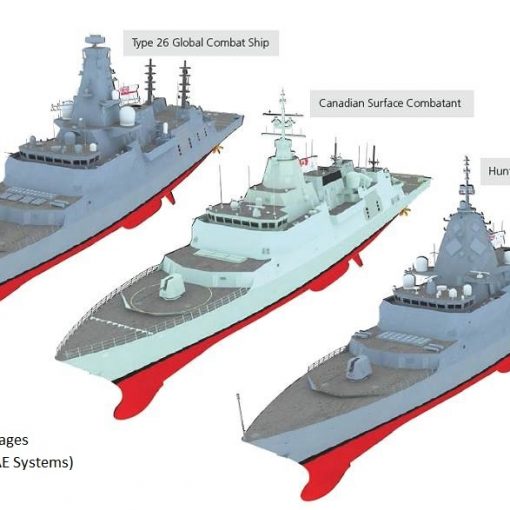

The main item of the NSS is the Canadian Surface Combatant (CSC), the one that is exposing the high cost of Canada’s lost capability to bring such an endeavour to completion. The Parliamentary Budgetary Office (PBO) recently released a report on the cost of the program. It uses well proven tools to evaluate the costs. The report also compared our program with other naval frigate building programs but that is a daunting task. While you would think that comparing one program to another would be quite simple, it is not. Canada incorporates everything in the cost calculation -- including building the ship but also the weapons, initial spare parts, management, infrastructure and almost everything you might think of. Other states only account for the actual construction of the ship without spares and only sometimes government-supplied items such as weapons or sensors. Foreign programs might reveal a totally different picture.

While almost all our allies use different classes of ship to tackle different task such as Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW), Area Air Defense (AAD) and Anti Surface Warfare (ASuW), Canada uses a single configuration common to all ships. It will provide us with great operational flexibility. Training and crewing will be simplified and will allow great cost saving in personnel training. It will be possible to face changes without calling for a different ship for support or for ships to be transferred from coast to coast.

One of the ship programs that the PBO report examined is the RN Type 31 frigate. That class of ship is to be a simplified version of the Danish Iver Huitfeld-class frigate and would complement the highly specialized Type 45 AAD destroyers and the Type 26 ASW frigates in their main task. They will notably use the same main gun as the Halifax-class frigates, two 40 mm gun and re-use 24 cell Sea Ceptor missiles from the recently upgraded Type 23 frigates. Another program that was looked at was the FREMM frigate developed commonly by France and Italy and built in many configurations specialized for ASW, general purpose or air defence capability.

However, it is the modified and yet-to-be-built US Navy variant (FFG)x program that is being used for comparison. This design is comparable to the Type 26 but it will have a slightly smaller displacement, lower range, lower cruise engine power and lower ASW focus. It is difficult to tell how much modification the ships would require to meet the Canadian SOR since DCNS and Fincantieri refused to bid within the official bidding process. It is hard to tell how much the enlargement of the ship might affect its overall performances just like it is with the Type 26. The FFGx is also not known to be equipped with the strike length MK41 vertical launch system (VLS) that might hamper the addition of future larger weapons to the ship.

Some comparisons have been made between the Canadian version and the parent design, the UK’s Type 26 frigate. There are significant differences. While the Type 26 will possess the same hull, propulsion plan and ASW attributes as the CSC, except for the missing ship’s torpedo launcher and a different towed array sonar, it will not possess an AAD attribute since that task is given to the Type 45 destroyers, and it will have no ASuW attribute beside the 127mm main gun. Worth noting is the fact that no weapons are yet selected to fit into the 24 cells MK41 VLS meaning that millions of dollars worth of missiles and their integration to the combat system are not include in the UK’s price tag. The ships of the class will also receive some equipment from the recently upgraded Type 23 frigates such as Artisan 3D main radar, towed array sonars and Sea Ceptor air defence missiles; a significant saving for the UK. This transfer of equipment from a generation to another can be related to the last iteration for an indigenous CSC concept displayed circa 2016 before it was decided to go for an ‘off-the-shelf’ design. The detailed model I saw displayed a probable reuse of the Electronic Warfare suite (EW), counter measures and Naval Remote Weapon System (NRWS) recently installed on the Halifax-class. The concept seemed to be using at least two gas turbines for a maximum speed of 30kts+, no multi-mission bay or surface-to-surface missiles (SSM) and strangely featured the Australian CEAFAR radar. One can wonder if we tried to compete against the Type 26 frigate for the Australian SEA 5000 program at that time.

If some are tempted to compare the CSC with an upper end ship, which was not done by the PBO, they might suggest comparing to the Arleigh Burke-class destroyers. With 68 ships completed by two different shipyards so far, they have maximized the learning curve, and regularly adapt to new upgrades such as the upcoming Flight III version. These ships are only about 4 metres longer than the CSC so putting both classes together should be about the same complexity. However once you have built 4-5 CSC and learned the process, it should be less expensive since the destroyer is fitted with 4 propulsion gas turbines and 3 electric generator gas turbines vs 1 propulsion gas turbine and 4 diesel generators for the CSC. Both ships use 127mm main gun, secondary guns, torpedo tubes, helicopter hangar and highly advanced sensors but the CSC will carry 32 cells MK41 VLS and 6 cells Extensible Launching system (Exls) vs 96 cells MK41 VLS for an Arleigh Burke Flight IIA or III.

Some concern has been raised about some of the equipment selected for the CSC such as the main 127mm gun. The gun that was referred to as being discontinued is not the 127mm gun but the BAE MK8 114mm gun that was last installed on the RN’s Type 45 destroyers. There are actually 2 127mm gun system produced in the western hemisphere -- the Leonardo 127/64 LW Vulcano and the BAE MK45 Mod 4. The latter is probably the one that will end up being installed on the CSC. This gun is to be installed on the other Type 26 variants as well as the upcoming Flight III Arleigh Burke destroyers and the Japanese 30FFM frigates.

The main concern is the selection of the SPY-7 radar as the ship sensor. This is to be the main asset of the ships, so no error should be allowed. While other contenders were excellent to face the existing threats, this one has the potential to face future hypersonic weapon that give little to no time to react. A first version of the radar is to go at sea on the Spanish F110 frigates circa 2026 and should help pave the way to a successful integration to the CSC. These upper end sensors should be considered as an investment into the future relevancy of our fleet.

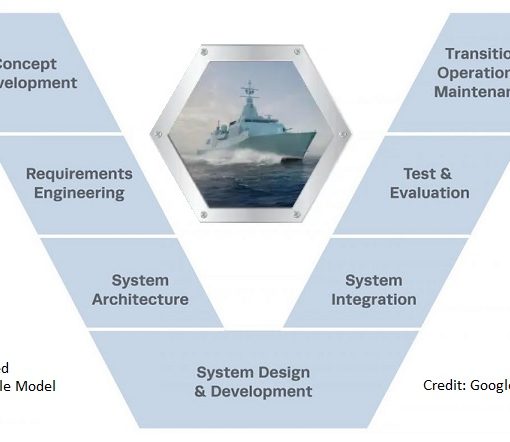

The Auditor General criticized the NSS program for all the accumulated delays and the risk of losing critical capabilities by the CCG and RCN. The decision to move from an indigenous design to an ‘off-the-shelf’ one in 2016 was supposed to allow for first steel to be cut in 2020; now first steel cut is expected in late 2023 at the earliest. The latest bad news concerning the program is an announced building time of 7½ years. The building time depends on the design itself but mainly on the skill set available, the physical capacity of the shipyard and the timely delivery of the main components that go in the structure as it is put together. If the physical capacity of the yard represents a bottle neck, one could be tempted to use over-time to speed up the process but that raises the cost of every worked hour significantly. One efficient way that was used on projects such as the Type 45 destroyers and QE-class aircraft carriers is to build entire sections of the ship in separate yards then put them together in a single yard. Building of, say, the front section of the ship could easily be outsourced to the third partner of the NSS. The sooner the ship’s sections are put together, the sooner you can start the process of cable pulling throughout the ships which links every part of the ship together. This could potentially shave off months of the building schedule. That technique also helps reduce the usage of over-time which is a major cost driver in any industry.

It is time that Canada’s shipyards put their fight aside to deliver a quality product at a good price to taxpayers. Cooperation would not cut down ISI’s profits since it originally hoped to build these ships in 5 years each on their own. To bring the building schedule closer to the originally envisioned 5 years per ship would also diminish the effect of inflation which is very high in the defence industry. One critical point to the schedule is the timely delivery of components such as engines, gear boxes, pumps and so on. That is where an efficient supply chain will make the difference. At some time, there will be Type 26 frigates under construction in three different continents and this will put pressure on timely delivery of common components. That will need to be closely monitored.

3 thoughts on “The CSC within the NSS”

Hi Mikaël Perron. Read your piece on The CSC within the NSS with great interest. Your comments about the PBO report on ship alternatives to the CSC makes lot of sense especially with the FFGX Constellation class frigate. Your attempts to compare the CSC with the AB class destroyers seems to be reasonable and I agree the BAE MK45 Mod 4 127mm gun will finally be chosen for the CSC. The very heart and sole of the CSC Frigate will be the SPY 7 (V) 1 LRDR and we must get this one right the first time. The radar going on the Spanish F110 Frigate first will definitely give Canada a great view as to how this RMA system will perform on the CSC Frigate and correct any faults before being fitted. Your suggestion to build CSC Type 26 Frigate large modules in a third shipyard (Davies?) would certainly help to bring the build time down to the original 5 year plan, save money and in the process, create a more viable NSS if shipyards could finally learn to work together, however I feel that Irving would not want to comply.

Hi M. Dunlop,

I totally agree that such a proposal would encounter much resistance. However, shipyards should remember that they are working for the Canadian citizen and the RCN. If they could demonstrate that, by working together, they could reduce cost of the NSS, they could hope to see further work in the form of a submarine replacement program. Hard decisions will need to be made in the submarine file, but a good performance on their part could lead to the local building of a foreign design submarine in a consortium of NSS Shipyards.

Hello Mikael Perron. Agree that shipyards should start working together, however Canadian Shipyards get contracts from the government for one reason. Although it would be nice to say that they work for the people of Canada and the RCN, as a civilian company, their bottom line is to make money for themselves and their share holders. Agree totally on what you have said WRT new replacement submarines. This can’t happen soon enough!!