By Peter M. Sanderson, 15 October 2025

According to the White House, President Trump has authorized the construction of up to four Arctic Security Cutters (ASCs) abroad. The President also signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Finland to construct these four ASCs in shipyards in Finland, then utilizing Finnish expertise to construct up to seven new ASCs in the United States at Bollinger Shipyards.

By agreement, the three tonnage classifications of ICE Pact icebreakers are: 26,000 ton, Polar Class 2, Heavy Icebreakers; 22,000 ton, Polar Class 2, Program Icebreaker (CA) or ASC (US); 9,000 ton, Polar Class 4 Multi Purpose Icebreaker. Just as Taiwan is known for chips, Finland is the center of excellence for these specialized, hard to build ships. The purpose of the friendly takeover by Chantier Davie, was keep the Finnish team together and working: design bureau, specialized steel, Helsinki yard and the supporting yard at Pori. The Helsinki yard construction hall is big enough to add the first ASC next to Canada’s first Heavy Icebreaker hull, which is presently undergoing construction.

Image: A graphic of the Multipurpose Icebreaker variant proposed by Seaspan, Rauma, Bollinger, and Aker for the US Coast Guard's Arctic Security Cutter. Credit: Seaspan

2 thoughts on “Under ICE Pact, the United States announces it will build their Arctic Security Cutters (ASC) first – October 9, 2025 ”

It’s encouraging to see the United States finally making tangible strides in Arctic security. The authorization of the new Arctic Security Cutters and the cooperation with Finland’s world-class icebreaking industry mark a real shift from talk to action.

This approach dovetails neatly with the broader North Atlantic and Arctic posture being developed under U.S. Second Fleet and NORAD modernization. A capable, allied U.S. Coast Guard presence in the Arctic strengthens not just American sovereignty, but the overall collective security architecture we share across the North.

For Canada, this should be seen as complementary rather than competitive. The ASC program aligns well with our own Polar Class and AOPS investments, offering opportunities for coordination in logistics, shipbuilding technology, and joint operations under the Arctic Council and North American defence frameworks.

It’s also worth noting that this cooperation keeps Finland’s icebreaker expertise viable after the Davie-Rauma partnership, an industrial win for all Arctic democracies. In the end, stronger allied capability in the High North benefits everyone who values a stable, rules-based Arctic.

The decision to build U.S. Arctic Security Cutters is a calculated effort to address a critical national security and sovereignty gap that has grown for decades.

While the strategic rationale is strong — driven by intensifying great-power competition and the opening of Arctic waters — the initiative must overcome a history of mismanagement and procurement failures. Its success will depend on whether the foreign collaboration model can effectively deliver ships on schedule and transfer critical expertise to revitalize domestic shipbuilding.

The U.S. Coast Guard’s current icebreaker fleet is outdated and insufficient. Before the new ASCs were announced, the Coast Guard operated just two active polar icebreakers, with the heavy icebreaker USCGC Polar Star being nearly 50 years old and in precarious material condition. The ASC program fills this critical capability gap by rapidly expanding the fleet.

Unlike previous failed attempts to build icebreakers entirely domestically, this program leverages international cooperation to accelerate construction. Partnering with Finland, a world leader in icebreaking technology, allows for the parallel construction of the first vessels in Finnish shipyards. This fast-tracks delivery while also revitalizing the U.S. domestic shipbuilding industry through technology transfer.

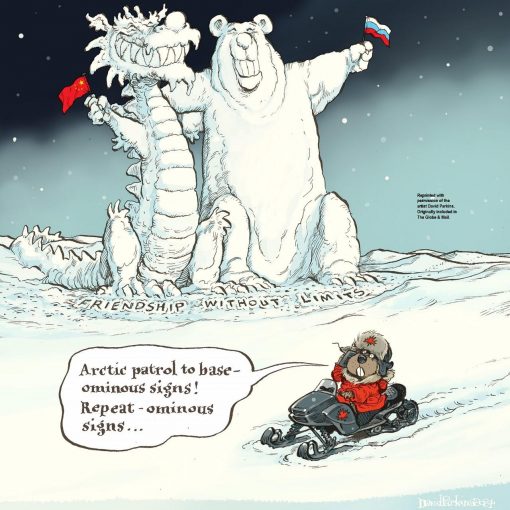

As Arctic sea ice recedes, the region is becoming a new frontier for international competition. Russia has built up a large fleet of icebreakers, including some that are nuclear-powered, while China has also fast-tracked its own construction. The ASCs will help the U.S. project presence, enforce sovereignty, and counter the growing military and economic influence of these rivals.

The new cutters are designed to support a wide range of Coast Guard missions, including national defence, maritime safety, search and rescue, and environmental protection. A larger and more modern fleet is essential for asserting American interests and protecting its territory in the High North.

However, the U.S. has struggled for years to build new polar icebreakers on its own. The Polar Security Cutter (PSC) program, established in 2016, was plagued by delays, mismanagement, and massive cost overruns. The first PSC is not expected until 2030, six years behind schedule and at nearly triple the initial cost estimate. This history of failure raises concerns about the feasibility of a new program.

Some analysts argue against focusing on a few large, expensive, and potentially vulnerable icebreakers. They suggest a diversified and modular approach, including smaller, ice-capable patrol ships that could be adapted for various missions. Other unconventional concepts, such as a polar submarine fleet, have also been floated as potentially more effective long-term solutions.

While foreign collaboration accelerates delivery, it represents a continued reliance on other states for critical shipbuilding expertise that the U.S. industrial base has allowed to atrophy. The long-term success of “on-shoring” this technology remains to be seen.