By Thalia, 20 September 2025

Lately, a curious ambivalence seems to be emerging about the state of Canada-US military relations. This ambivalence has revolved around Ottawa’s much delayed F-35 fighter jet purchase, but has been extended to other military equipment acquisitions as well, notably the River-class destroyers.

On the one hand, Prime Minister Carney has stressed that we have reached a major turning point in this relationship to the point that our old Cold War assumptions of close cooperation have become a source of vulnerability. The PM has indicated that, as a partial solution to this dependency, in future Canada should reduce this vulnerability via a ‘Buy Canadian’ policy and more reliance on non-US defence links.

Conversely, many prominent defence commentators, including former DND officials, allege that for a variety of reasons, Canada cannot afford to renege on its F-35 deal with the United States. In particular, they claim that any change now would jeopardize the longstanding principle of close cooperation with the United States in continental defence.

The nub of the issue seems to be differing interpretations of how serious and how permanent this rupture in Canada-US relations might be. Some commentators seem to fall into the camp of doing nothing to upset the Americans, and that all will be well between our interoperable militaries because they always have been solid in the past. But how can Ottawa square its stance of proclaiming a major ‘disruption’ with the United States and the resulting need to procure systems from non-US sources with the argument that we have no option but to rely on the United States for our defence because we always have since WW2, largely because we cannot afford to defend ourselves on our own?

Many who make this latter argument also staunchly believe that Canada has near total freedom to act as it wishes regarding its defence actions.

So which is it to be? No option but to rely on the United States and its equipment, or dare to reduce our dependency by seeking fewer US-made weapons? Inevitably, there will be voices proclaiming Ottawa can do both -- then the issue becomes, when, if ever, will we act to be less reliant on US equipment and doctrines?

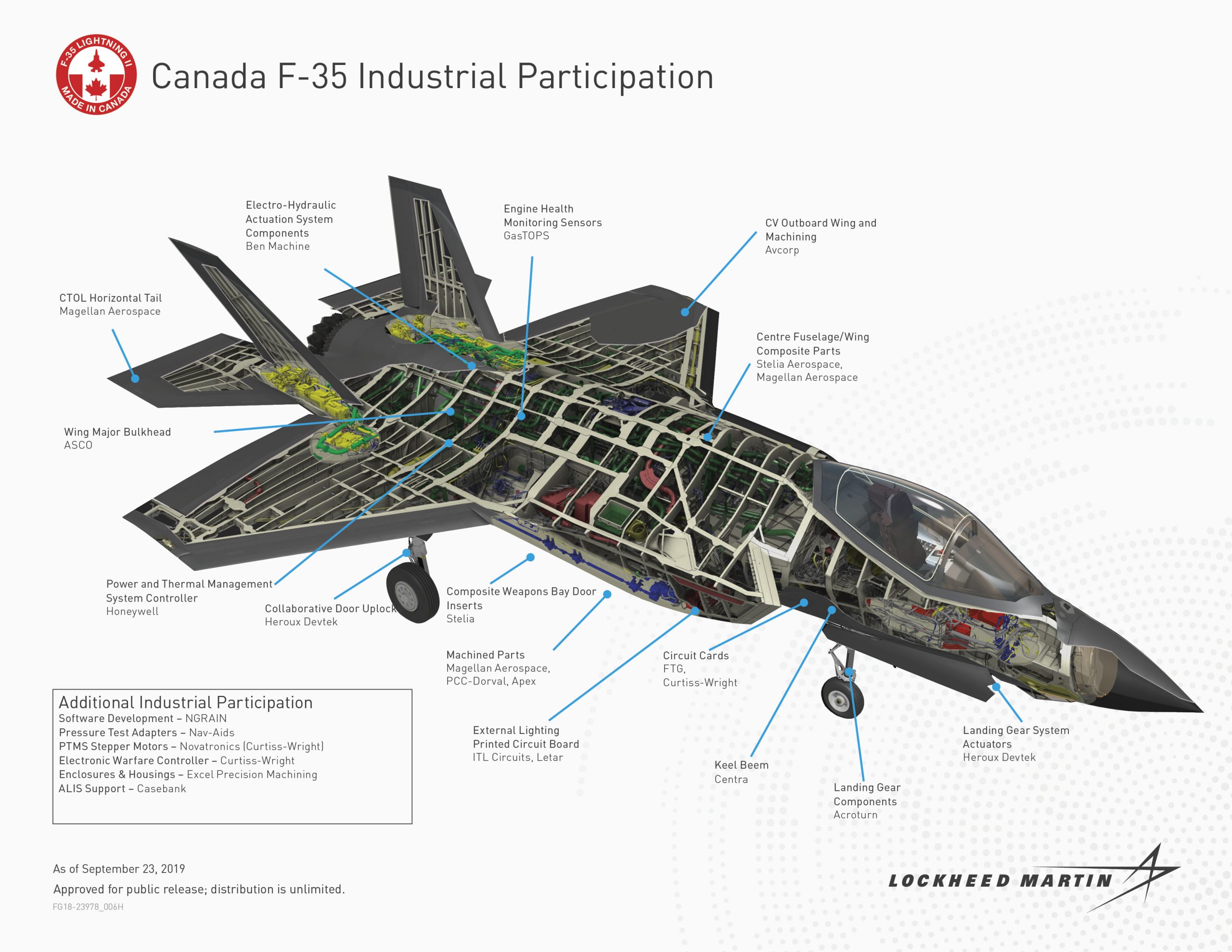

Image: An infographic of Canadian industrial participation in the F-35 program from 2019. Credit: Lockheed Martin

9 thoughts on “Can DND think outside the US defence box?”

I think many senior Canadian military officers take a long term view. They have been in the military since a young age, and now decades later, they have seen governments come and go – and come and go – and come and go – with each government pushing its own agenda, based on what the government believes its voter mandate allows. Not only Canadian governments, but also foreign governments.

However the military is charged with the defense of the nation and know quite well that the next government in Canada and also south of the border (or an ocean away) could change policies. Canada’s top military leadership also know the foreign military they deal with, have senior officers who also have a long term view, and who know quite well that political agendas of a country can change at the occurrence of the next democratic election.

Hence to the maximum extent permissible, the military try to foster good long term relations with the military of our allies to compensate for the variations in democratic politics and trade. Having common military equipment is a major cost saver and major factor in ensuring higher operational capability. This is especially true for a country whose military has been massively underfunded for decades.

Once one goes down a certain road for a military procurement, to change procurement … in essence to change horses in mid-stream, the road becomes fraught with risks and massive cost over-runs, over-runs that will both hurt the Canadian tax payer, and hurt the Canadian military, especially if there are inadequate funds to cover the over-runs. Hence cost over-runs, and hence changing horses in mid-stream, is a very bad idea – and it should be avoided.

Consequently, I think current commitments to buy military hardware should continue, unless, obviously, the seller massively changes the price of the equipment to no longer make it viable. But if the seller changes the price (or applies tariffs) in an unrelated to the military procurement, once we are mid-stream, to change the approach only hurts Canada, more than it hurts the military equipment seller.

The application of trade measures needs to be applied carefully, and in the case of the F-35 and equipment for the River Class Destroyer, I believe we need for the benefit of Canadians to continue on the current approach adopted by the senior Canadian military.

Good afternoon Lee,

Interesting points.

I think, though, that Canada must first rethink/reaffirm its grand national strategy and then determine how much any particular piece of equipment fits into it. We must not put the “picking the equipment shiny baubles” ahead of the “what are we trying to accomplish” stage.

This effort must consider which countries are now the greatest threats to Canada and how they must be resisted.

Ubique,

Les

“I think many senior Canadian military officers take a long term view. They have been in the military since a young age, and now decades later, they have seen governments come and go – and come and go – and come and go – with each government pushing its own agenda, based on what the government believes its voter mandate allows. Not only Canadian governments, but also foreign governments.

However the military is charged with the defense of the nation and know quite well that the next government in Canada and also south of the border (or an ocean away) could change policies. Canada’s top military leadership also know the foreign military they deal with, have senior officers who also have a long term view, and who know quite well that political agendas of a country can change at the occurrence of the next democratic election.

Hence to the maximum extent permissible, the military try to foster good long term relations with the military of our allies to compensate for the variations in democratic politics and trade.”

I would counter this by saying many senior Canadian military officers seem to be blind to what has been going on, and have fallen back on denial as a coping strategy, and are still persevering with an old orthodoxy that is basically dead already. De jure, yes we are in treaties that require blah blah blah; meanwhile de facto, the logical foundations of those alliances have been washed away by a tsunami of outlaw behaviour from the regime to our south. Assurances of trust, gone; recognition of mutual interests requiring cooperation, gone; even respect for the sovereignty and right to exist of their allies is now gone.

Our CAF officers imagine the change within the USA and its attitude towards other nations is just some temporary thing, laugh it off as capricious domestic political posturing, and refuse to believe that it is a major long-term change to our neighbour’s ideological basis & strategic posture. Meanwhile, the US regime has been rapidly checking off box after box in the “How to become a totalitarian dictatorship” checklist.

I could list a dozen danger signs from historical experience, but the point is: the only reason our own national security community ignores those or does not judge them objectively is that it is the USA it is happening to this time.

They ignore the context of the US political system decaying deeper into open corruption and ideological extremism over the past 25 years. They ignore every red flag of an outlaw regime with clearly no respect for anyone, consolidating its power at home and showing belligerence to almost every other nation abroad. They ignore that it has been trying both overt and covert actions to influence & usurp other governments (and already gotten caught doing so in multiple places). It is a regime motivated only by what it thinks it can take from others, and that regime’s hostility towards Canada is not only crystal clear, but strategically irrational.

Our officers assume that their US counterparts are going to take a more sane long term view of those political factors, but without realizing that those US officers are also products of it. Well their government, their top-most chain of command, violates assurances of trust quite proudly, like other countries were suckers for ever believing in that at all. But that is what builds alliances and the sudden reneging on that trust is what destroys them.

If the US has become a rogue state, not respecting anyone else’s interests or sovereignty, perhaps no longer even capable of acting in good faith or understanding consequences to their own country when they violate every assurance of trust, that does not just dampen Canada’s alliance with them, it destroys the whole basis of it. Allies do not threaten each other with annexation and launch aggressive economic sabotage with that goal in mind. Allies do not deal in bad faith by changing allegiances mid-course and extorting other allies on behalf of adversaries. This is not just ‘policy instability’ or leaning into more self-serving conduct – it is treachery; it is adversarial conduct. Therefore what does that make them? (Go on say the words.)

From what I have seen our military brass are just not psychologically coping with it. They simply do not want to believe the degree of danger to Canada is real, because our own defence establishment has been marinated in the ‘Canada/US Alliance’ orthodoxy since the 1940 Ogdensburg agreement. Literally none of our officers have ever experienced anything else in their careers, so they cannot even imagine a condition where Canada cannot trust its neighbour and might even have to defend itself against that neighbour (which just happens to be the only other country that has ever attempted conquering us before).

So as it relates to procurement, there is far more than just the usual ‘defence spending levels’ and ‘technical interoperability’ arguments to hash out anymore. Trust underpinning our most central alliance relationship has been broken, the main tenets of our strategic orthodoxy lie dead and rotting, and we are stuck dealing with unprovoked betrayal and irrational hostility. It’s not due to anything Canadians have done, but if our neighbour has lost its collective mind and fallen into tyranny, we have to be cold-blooded realists about it and not make defence decisions based on some kind of hollow sentimentality.

Our CAF leaders cannot just cloister themselves away in some DND offices and pretend that the most ominous political changes since the 1930s are not happening to the world right now. There is no way that under such conditions that Canada should be buying any more US military hardware, nor operating our military as if the most important thing is aligning our capabilities to complement theirs. We must stop rewarding the Americans’ misconduct against us with any of our money. For a while, we may be stuck buying certain systems of theirs that have already been decided on or paid for, but that must be a temporary condition we strive to end. We can and should need to look elsewhere for any other systems that can meet our needs without them being involved. We must boost our own defence manufacturing, so we can be more self-sufficient and also act as production partners of those other allied nations that are still trustworthy. It will take aggressive and sustained effort on our part, but the rising threat against Canada makes it necessary.

A further point – where above it is noted “So which is it to be? No option but to rely on the United States and its equipment, or dare to reduce our dependency by seeking fewer US-made weapons? Inevitably, there will be voices proclaiming Ottawa can do both — then the issue becomes, when, if ever, will we act to be less reliant on US equipment and doctrines?”

Don’t think we only buy from the USA.

Take a look at the Canadian Patrol Submarine project. Are the two finalists from this very expensive program from the USA?

No.

German TKMS and South Korean Hanwha Ocean have proposed two excellent submarine candidates to meet Canada’s maritime requirements for submarines. Neither of those are from some USA defence box.

Take a look at the drone being procured for the Halifax frigate. To the best of my knowledge, that is not being procured from some USA defence box.

As for the River Class Destroyer, yes, some equipment (such as Aegis, AN/SPY-7, and SLQ-32) are planned to come from the USA, but in general the Type 26 (on which the River Class is based) is not provided by, nor is it being procured by the USA. It is the UK Type 26 that Australia is also adopting (with their own modifications) and Canada as well (with RCN modifications) adopting.

So we are not caught in some US defence box. The military selectively chooses what is believed best given the limited funds promised.

Further if it behooves Canada to adopt a USA approach for selected equipment in some cases, where for the benefit of the Canadian taxpayers, and for the benefit of the men and women we want to defend our country, that we should ensure we procure equipment best able to support them to, if unfortunately necessary, lay down their lives for us. Aegis/AN-SPY-7 (from the USA) opens up the opportunity for Canada to participate in CEC and C2BMC functionality, greatly enhancing the effectiveness of the River Class destroyers. Choosing the SLQ-32 EW system, reduces the integration costs that may have occurred had Raven ECM been procured instead. These are financially and militarily sound approaches … with a long term view. A view that is good for the defence of Canada.

I think that most Canadian military leaders (except General Blondin) would agree with you and would prefer to stick with tried and true, and often superior, US-made weapons systems.

But I see now that I should have titled this item as ‘Can Ottawa think outside the US defence box?’

My concern is the political dimension of Canadian defence procurement.

The Carney government has made a point of declaring that Canada needs to reduce its current reliance on the United States for the bulk of its major defence purchases in light of the current trade dispute, and presumably because the US is no longer considered a reliable ally. The Prime Minister has created a new position, Secretary of State (Defence Procurement), in order to assist in this regard.

Beyond the on again, off again F-35 deal, Ottawa has initiated a number of major military purchases with the United States – the P-8 patrol aircraft, the aerial tankers, the MQ-9B drones, and is about to proceed with the purchase of Army HIMARS systems. In addition, the River-class destroyers will incorporate many key US systems, including the radar, sensors, battle management systems, missiles (except for the Naval Strike Missile), and torpedoes.

If these US weapons – worth many tens of billions Canadian – are to be excluded from Ottawa’s ‘Buy Canadian’ initiative, then what is left? Up to 12 submarines, and maybe a similar number of Continental Defence Corvettes down the road. OK, not insignificant I admit. But my point is that DND is going to be operating most of the equipment noted above for 30 to 50 years so what major opportunities remain to apply the new ‘Buy Canadian’ policy?

My question remains. If Ottawa is serious about bringing in a ‘Buy Canadian’ policy, will it have to act on at least some items in the current roster of US-made weapons systems?

Good morning Thalia,

The key questions seem to be:

– what is the grand national strategy driving Canada’s defence plans?

– does “Buy Canadian” mean only buy whatever we can build in Canada?

– are there credible non-American suppliers for the defence systems the CAF needs?

Depending on the answers to these questions the scope for diversifying Canada’s defence investments could be quite broad.

Ubique.

Les

Hello Les Mader,

I agree with all the points you raise. Your questions are spot on.

I think there are several different motivations behind Ottawa’s current ‘Buy Canadian’ policy. Playing to a domestic audience is likely one, and, despite our well trained Canadian military, it is also true that our governments have not always procured the best military equipment because either those weapons were not available to us (the F-22 for example), or they were judged to be simply too expensive (nuclear-powered submarines). Also, we must remember that to be interoperable with the US does not necessarily mean that we have to have identical weapons and combat systems to those of the US. Rather the goal is to be able to work effectively with our main allies, and we have managed that rather well in the past.

The crux of the matter is that our government leaders no longer believe that the previous security system of alliances and coalitions anchored by the US prevails in today’s world. Our political leaders judge that the US can no longer be trusted to be a reliable ally and arsenal of democracy, and so they are trying to find ways to adjust prudently to this new strategic reality.

I sense that these same leaders recognize that diversifying our procurement suppliers and seeking more reliable defence partners will entail some considerable hardship to the CAF, especially in the short-term. But this new strategic landscape is one that is being shaped by the United States not ourselves, and so adjust we must. To do otherwise and try to wish away the new reality will do more harm to our military in the long-run.

Lately there’s been talk of a supposed turning point in Canada–US defence ties, sparked by the delayed F-35 purchase and future River-class destroyers. The claim goes that Ottawa either clings to US kit out of habit or breaks free through a ‘Buy Canadian’ policy and new non-US partnerships. That tidy either/or makes good copy, but it’s not how Canadian defence policy works, nor how allied militaries operate.

There is no evidence of the dramatic ‘disruption’ the Prime Minister’s rhetoric is said to imply. NORAD modernization is moving ahead with record Canadian investment. Canadian firms remain deeply embedded in the F-35 program and Five Eyes cooperation is steady. Procurement disagreements are normal among allies; they are not a strategic break.

Ottawa’s longstanding goal is to maximize domestic work inside allied programs, not to wall the country off from US technology. The F-35 itself proves the point — Canadian industry benefits precisely because Canada is inside the program. River-class destroyers follow the same pattern: built here, drawing on proven allied combat systems.

Continental air defence and NATO commitments demand compatible data links, weapons and command systems. Swapping to non-US suppliers to make a political statement would drive up costs, lengthen timelines and weaken readiness. That is strategic self-harm, not sovereignty.

Canada does not have the design base or fiscal headroom to field fifth-generation fighters or Aegis-class warships on a purely national footing. To pretend otherwise is to ignore decades of industrial and financial reality.

For generations Canada has followed a blended approach: build ships and infrastructure at home, integrate proven allied combat systems, and share R&D with trusted partners. It is neither dependence nor isolation — it is a conscious strategy suited to a middle power with global obligations and finite resources.

The real story isn’t ambivalence; it’s consistency. Canada will keep investing in its own yards and technologies where it makes sense, and stay locked in with close allies where operational demands require it. That’s not indecision. That’s sound strategy.

There is an engrained tendency to want US equipment in the CAF for a myriad of reasons, not the least being a deep connection and exchange program between the countries as Five Eyes members. The exchange program is useful for both sides – Canadians get exposure to doctrine and advanced concepts as well as genuine advancements in operational integration. In return the US get early converts to their military supply chain and the eventual rise of officers into decision influence space within the CAF and in the Canadian defence industry – it’s a great marketing strategy.

There is no doubt that US produces some excellent systems, but they don’t necessarily produce the best system across all capabilities, either on a pure technical basis or simply from an operational employment context. Also their acquisition philosophy relies on a system of systems approach to solve a problem. E.g the F22-F35-EF18G-EC135RJ-E3-JSTARS approach to air operations.

Canada needs to be more mature and not take the easy route as we simply will never be able to afford the ‘systems of systems’ approach across any service. We need to have a serious conversation on our defence policy, which hasn’t occurred under SSE or even ONSAF. They have to a large extent been a shopping list. Only when clear defence policy arises and the CAF then does the hard-nosed analysis to what this means as far as resultant capabilities will we make better informed decisions, rather than be ensnared by our tendency to take the somewhat lazy approach and default to ‘buy American’. The decision may still be to buy US equipment, and almost assuredly a significant portion of our capabilities will be US originated due to their preponderance in the market. Nevertheless, especially in today’s world where interoperability, to a very large part, hinges on common data exchange protocols, NATO STANAGS enable this. We should therefore objectively evaluate how a system works for Canada’s defence objectives and not be intimidated by a false spectre of not being interoperable if our specific systems aren’t exactly the same. The F35 vs Gripen debate is once such example. The River Class may be somewhat different as the AEGIS/SPY-7 system is amongst the best, if not the best and solves a number of Canadian needs for IAMD in a proven manner.