By Roger Cyr, OMM, CD, 11 January 2022

The federal government is planning to build 15 new frigates, the British Type 26. This is good news since the navy estimates that the present frigates are nearing the end of their operational life. However, according to a report released in December 2021 by the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO), the costs for the new frigates have skyrocketed and the delivery of the ships will be delayed by decades.

It is a fact that building ships in Canada is more expensive than buying off-the-shelf from an offshore supplier. But, the reason they are built in Canada is to hopefully create a domestic supply chain with increased employment, intellectual property and industrial capacity. With the Type 26 frigates there will likely not be a domestic supply chain since all the machinery and combat systems are provided by offshore suppliers. The PBO report states that labour costs in Canadian shipyards are 55% higher than in the United States. The bottom line is that whether procuring these ships abroad would entail significant savings, or whether these savings would be sufficient to offset the loss-benefit to having a made-in-Canada fleet which will employ thousands of workers.

There are many political constraints to consider with all naval construction. There is the geopolitical situation with respect to contractors so that it serves government political objectives and public perceptions. These constraints affect the cost or delay in construction. Looking at the navy’s new Joint Support Ships, which are already years late and billions over budget, the PBO estimates a one-year delay in construction of the two vessels would add $235 million to the overall cost increase while a two-year delay would result in a $472-million and add years to the timeline for the building of the two ships. It is obvious that the government’s drive to build ships in various yards in Canada rather than procuring the ships overseas comes with a significantly increased cost and with a huge delay in production

It is a much worse situation for the new frigates. Construction of a new fleet of 15 frigates was estimated to cost $26.2 billion in 2008, it is now expected to cost as much as $82B, according to an analysis by the PBO. There is talk about looking at other alternatives for procuring the frigates. However, the Department of National Defence issued a statement saying reopening the current contract is not an option and that it remains confident in its estimate of $56 to $60B. It indicated that the Type 26 is the right ship for the navy and construction remains on course to begin in 2024. It is estimated that it will take seven and a half years to build one ship, with the first ship to be delivered to the navy at the earliest in 2031. This is partly because Britain, Canada and Australia are still feeling their way around how to build this ultra-modern warship.

The Royal Navy planned to build 32 of Type 26 frigates, but sticker shock lowered that number to eight, while the Australian navy plans to buy nine of them. The RN’s first Type 26 is to be delivered in 2023. With 15 ships to be built by Canada, it would have the world’s largest fleet of Type 26 frigates.

There is an alternative, and this is to take a proven offshore design and build the ships in one Canadian shipyard. A strong candidate for this option is the Frégate européenne multi-mission or FREMM. At least a dozen countries have chosen the FREMM for the decades ahead, including the United States.

The FREMM is a family of multi-purpose frigates designed by Fincantieri and Naval Group for the navies of Italy (10 frigates) and France (8 frigates), and also for the export market. The lead ship of the class Aquitaine was commissioned in November 2012 by the French Navy. Italy has ordered six general-purpose variants and four anti-submarine variants. France has ordered six anti-submarine variants and two air-defence variants. They are being built in their respective countries.

According to the French Armament General Directorate (DGA), FREMM, designed and developed by Naval Group, is a stealth, versatile and enduring surface combatant with advanced automation. Its main missions are the control of a zone of maritime operation, anti-surface warfare and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) precision deep strike with naval cruise missile. It is the only class of NATO ships in Europe with the capability to launch land attack cruise missiles from surface vessels. The FREMM has an overall length: 142 metres, displacement: 6,000 tonnes, maximum speed: 27 knots

In September 2017, a variant of the FREMM was offered directly to Canada. This direct bid included delivery of the first ship in 2019 if accepted within the year and a fixed price of $30 billion for all 15 ships, versus the $62 billion then estimated for the government’s prime-contractor ship building plan for the Type 26. The offer was rejected, citing the unsolicited nature of the bid as undermining the fair and competitive nature of the procurement. In October 2018, the Type 26 design was chosen by Canada as the winner of the program and a contact was signed to build the frigates. Selecting the FREMM instead would have resulted in a saving of some $30B.

On 30 April 2020, the US Navy announced that Fincantieri had been awarded a contract for the first FREMM, to be built at Fincantieri Marinette Marine in Wisconsin. The USN renamed it the Constellation-class frigate, and awarded a follow-on contract to Fincantieri to build a total of 10 frigates for $16B (US), which works out to about $1.6B (US) per ship. Construction of Constellation will commence in 2021 following the final design review. The ship is expected to enter service in 2026.

Comparing these numbers with the Canadian Type 26, government estimates peg the cost of 15 ships at $62B, or $4B per ship, and 20 years to build the fleet. If the current contract for the Type 26 goes ahead, construction of the new frigate fleet would begin in 2024, with delivery of the 15th ship in 2045. There are now concerns that today’s 12 CPF frigates in their present conditions will not last until the new Type 26 become available. Thus there will likely be a period that Canada will not have sufficient combat capable ships. It would leave the country vulnerable and not able to meet its NATO and international obligations. The Type 26 is not a proven design since there is no ship in service at this time. Yet the FREMM is proven and has shown its combat worthiness.

In 2021, the French Navy FREMM Frigates FS Provence and FS Languedoc won the US Navy’s ‘Hook’em’ award. This was the second year in a row that the US 6th Fleet awarded the trophy to French frigates for their ability to find and track submarines. The prize rewards anti-submarine warfare (ASW) excellence. The FREMM have demonstrated superior ASW readiness, proficiency and operational impact.

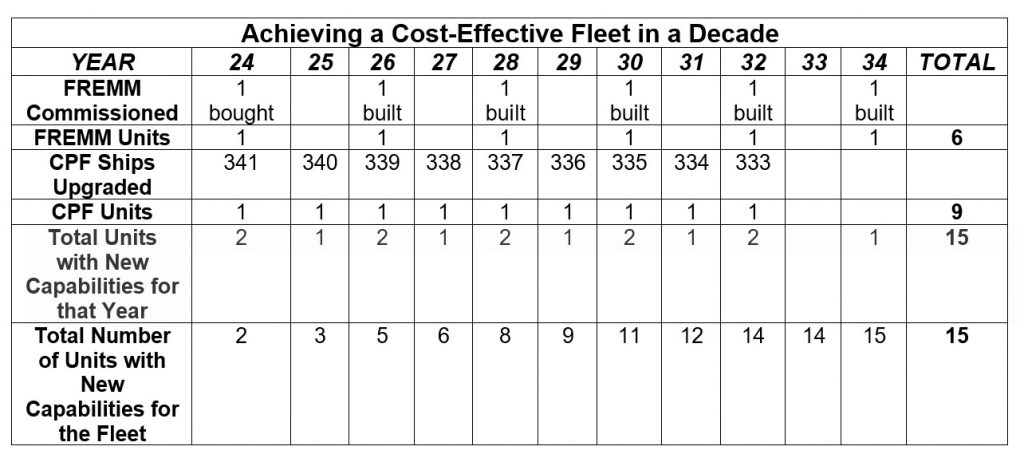

These ships can be procured as the Canadian Surface Combatant (CSC) at a lesser cost than the Type 26 and be available earlier. Should it be decided to go with the FREMM, then there would be a significant reduction in the cost of new frigates, in the range of at least $20B. The FREMM would also be available sooner and an increase in the operational capability of the fleet. Canada could buy the first ship offshore and build the remainder in Canada. The saving would be available to upgrade the existing Canadian Patrol Frigates (CPF). The upgrade could be handled by other Canadian shipyards while the Halifax Shipyard concentrates on tooling and building the CSC. There would be a two-prong process, one yard building the new frigates, and other yards extending the operational life of the existing frigates. There would be a continual process of upgrading the fleet and limit periods of fleet operational paucities.

The existing frigates (CPF) were commissioned from 1992 through 1996, and are now 30 years old. The fleet upgrade should start with the last ship to commission, which is pennant number 441 and go up the list with 340 and 339 next. Once a new CSC becomes available, then the crew of a CPF would be transferred to the new ship and the old ship paid off, and so on until all the existing frigates are replaced by new ones. Over a 10-year period, Canada would have a modern and effective fleet of frigates. By 2034, the fleet would comprise 6 CSC, 9 CPFs upgraded with life extension systems, and 3 of the existing frigates. The required number 15 would be eventually reached, and all the CPFs would be paid off.

It needs to be remembered that the next decade is one of significant risk. It is agreed that the international security environment is becoming more unstable. This instability is clear in the maritime domain, particularly with the rise of more assertive states, grey zone warfare and technological risk. The navy is being asked to take on increasing responsibilities around the world. What is needed is a realistic assessment of capability against government ambition. This is not the time to have Canada’s navy not being able to respond to its international obligations and commitments.

23 thoughts on “Achieving a Cost-Effective Fleet in a Decade”

Don’t forget Fincantieri of Italy offered 15 FREMMs for a fixed price of $30 billion. The first one or two would’ve been in service by now.

It was proven by the PBO report last Feb that the actual costs from this unsolicited “bid” was actually over 70 Billion. If we did go that way they still would have been built by Irving and we still be waiting.

I suspect that Naval Group/Fincantieri threw that Hail Mary pass because of what was going on in Europe – namely the on-going effort to consolidate the industry and build a pan-European ship-builder. Once these two firms decided that they were going to submit a consolidated bid rather than have their respective FREMM designs compete against one another, they emerged from their huddle only to discover that there were no worthwhile industrial dance partners left over in Canada. Knowing the importance the client placed on involving Canadian industry, they did the only thing they could – make a phantom offer in the hope that Ottawa could be lured away from the process it had placed such faith in. It succeeded in deceiving some credulous journalists and analysts, but it was never going to work.

The FREMM alternative might be a cost-effective way to keep up the RCN fleet. Yet many of us believe it is not going to happen in the near future. I also assume that the european systems, from 50Hz equipment to Sylver VLS (instead of mk41), combat systems and radars, would not be to the pleasure of the RCN, therefore the US FREMM variant (Constellation class frigates) would better fit Canadian requirements. PBO report issued last February,already stated that building the Constellation class frigates in Canada would not bring significant savings (grossly 8% per ship) compared to the cost of building the surface combatants based on the Type-26.

The main advantages of building a sort series of FREMM-Constellation frigates, over other options to “bridging the [CSC] gap” explored in a previous thread would be that, unlike the Hobart batch-II proposal, building is already going to start within this year, and unlike the A. Burke proposals, it might be easier both to get the approval from the US government to have access to their platform design and technology, as well as to find a production gap or an agreement for joint production. Let’s note that the option for a second shipyard to build these frigates is under study in the US. The current location where these frigates are to be built, Marinette (Wisconsin, lake Michigan) also facilitates a lot for Canadian shipyards like Davie (QC) or Heddle (ON) to work on complete block packages to be delivered through the waterways to the US shipyard for final assembly, or maybe any other form of collaboration that might be agreed upon in order to enhance the Canadian content if not fully built in Canada.

These frigates, endowed with SPY-6 radar and 32-cells VLS, would not match the future CSC capabilities nor would deepen her magazines. Instead, if timely ordered, they would very well serve to bridge the gap until the first CSCs were delivered.

Hello,

About “would not match the future CSC capabilities”, could someone provide a comparison between the SPY-6 and SPY-7? Both are AESA, both are S-Band, one is Raytheon, one is LM, both contractors advertise their respective systems as the best super-duper, most versatile, most powerful in the universe. What known technical specifications make SPY-7 higher capability than the SPY-6?

Also, 32 VLS or 38 VLS, both layouts would carry subsonic Tomahawk or low-range supersonic RIM missiles of some kind.

Are these two aspects game changers?

Curious Civilian… you’re right, to compare both radar systems we need tech. specifications. It’s my fault not having detailed further what I wanted to state, just because my intention was to be brief. Actually, the comparison should have been between Constellation’s SPY-6(V)3 and CSC’s SPY-7 radars. The first is three-sided (3 array faces only), each with 9 RMAS (modules). For reference the Arleigh Burke flight III are being fitted with 37 RMAS per array (SPY-6(V)1 variant) and A.B. flight IIA are being retrofitted with SPY-6(V)4 variant, 24 RMAS per array. Accordingly, range and sensitivity of the (V)3 variant may be expected to be lower than those fitted in the Burkes. According to Raytheon’s own web [1] this (V)3 radar misses out defense against ballistic missiles and provides self-defense capability only. This should not be surprising, since the US Navy have other vessels (destroyers and cruisers) better suited for area-defense AAW.

On the other hand, specific data on the CSC’s SPY-7 radar is scarce, nevertheless since the CSC are designed to provide state-of-art AAW capabilities, it can be assumed those capabilities will be, at least, at the level of SPY-6(V)4, most probably beyond that.

Finally, 32 VLS or 38 VLS was not my focus. Indeed the 6-cells difference is for CIAD (close-in air defence) vs. RAM CIWS, 24 CAMM missiles vs. 21 RIM-116. While CAMM missiles seem to outperfom the latter in speed and range, again I agree with you, that’s not a game changer. My focus was actually on the last part of my sentence “(…) nor would deepen her magazines”, in reference to the previous proposals discussed under “Bridging the [CSC] gap”, based on the notional AB Flt III and Flt IV Canadian variants (64 VLS cells each) or even the RAN’s Hobarts (48).

[1] https://www.raytheonmissilesanddefense.com/capabilities/products/spy6-radars

Hello Curious Civilian. Unfortunately Lockheed Martin will not disclose the “weeds” of the SPY 7 V(1) radar systems characteristics for either the CSC, Spanish F110 or Japanese Frigates as they are proprietary and they would not want Raytheon to get any advantage. Yes Raytheon is a bit more forth-coming with the SYY 6 (V1) details and it is a great radar, but so is the SPY 7 (V1). If it weren’t “up-to scratch” Canada would not have bought it. The SPY 6 would also be a bit too top-heavy for the CSC mast as well. Also it is now known that the CSC Frigate will only have 24 MK 41 VLS cells vice 32. The other 6 VLS canisters are the CAAM missile silos aft of the funnel bringing the total number of cells up to 30 and not 38.

Roger,

I applaud you for thinking about how to speed up the existing glacial (stalled?) procurement process to get badly-needed new warships for the RCN.

The inescapable fact is that Ottawa, the Navy, and Canadian shipbuilders simply cannot deliver warships on time and on budget. Despite claims to the contrary, even the much lauded Halifax-class ships were delivered late (10 of the 12 were behind schedule) and over the original budget. It was not until the Overall Amending Agreement was negotiated in 1994 that the CPF program got back on track. Government claims against the shipbuilder were waived and a firm, fixed price contract was imposed almost after-the-fact to get this accomplished.

The problem is the insistence on a build-in-Canada approach under the National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS). Our shipbuilders appear to have little incentive to deliver ships on time and within budget. So, simply taking a more developed foreign design and bringing it to be built in Canada will not solve this perennial problem. Canadian shipbuilders will surely turn a much cheaper warship into a very expensive one.

Your suggestion regarding the current U.S. Constellation-class frigate perhaps provides a solution. The U.S. Navy at present plans to to build these frigates in two batches of 10 ships each. When Ottawa procured the C-177 strategic airlift aircraft for our Air Force, it managed to negotiate a deal to have the 5 initial Canadian aircraft integrated into the U.S. production line. This had the added benefit of allowing Canadian aircrews to train on U.S. C-17s ahead of their delivery to Canada.

Like many others contributing to this Forum, I am increasingly resigned to the political reality that Ottawa will likely continue its plans to have the initial 3-4 ship batch of the Canadian Surface Combatant built in Canada, even at their current exorbitant cost estimate, and possibly with some drastic reduction in their capabilities. Governments simply do not like to admit that they have made a mistake, and, to be fair at least part of the blame for the continuing delays and cost increases rests with a broken procurement system that nobody seems to have the ability or desire to fix, and to the entirely unforeseen impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic.

So, let us build the first batch of the CSC Type 26 in Canada, and perhaps even pay the shipbuilder extra to do it. But as you suggest, this will provide time for Ottawa to negotiate with Fincantieri Marine to get one or two frigates for the RCN inserted at the end of the first batch of 10 in the U.S. and then slot the remaining 10 frigates for Canada in at agreed upon intervals in the re-competed second batch in the United States.

Canadian suppliers could still compete to supply key components of the frigate, and Canada could benefit from learning curve production savings.

If Ottawa can pull this off, then Canada would get its new fleet with a warship better suited to Canada’s real maritime needs – that is, taking care of our own backyard, rather than bluewater tokenism – in a much more timely and cost-effective manner.

I think part of the ‘original sin’ of NSS was also the objective of establishing a domestic ship-building industry that could ride out boom and bust cycles. Surely this was misconceived. Once the current boom or CCG and RCN work is finished there is unlikely to be any more government build work for at least a decade – more than enough time for builders to despair of their prospects and close up shop. This perhaps could be mitigated by repair and overhaul, but that’s not the same as assembly. Or, perhaps if there was any chance of supplying complete vessels for foreign clients, but I see no inclination of Canadian governments to market the ware of the builders. We’d need a different strategic and corporate culture to replicate the success of, say, Damen in the Netherlands, which forms a kind of technological triumvirate with the Royal Neth Navy and the Defence Materiel Organization (DMO). Indigenous ship design capability, electronics and systems integration (Thales Nederland) and a willing partner in government has resulted in foreign sales of both new and used vessels, keeping the builder busy.

Of course, the Dutch approach works because there is a SINGLE going concern. This helps ensure that the industry is not plagued with over-capacity. NSS decreed two concerns would be tasked with building ships, but this has risen to three if I’m not mistaken. Sure, this capacity helps advance many long-delayed programs concurrently, but it will very likely be unsustainable once the current boom time is over. Thus we see the deliberate flaw in NSS – it did not seek to specify the scale of Canada’s allegedly ‘future-proofed’ ship-building industry. That would be left to a government in a far-distant future. But if a BUILD capability is to weather the inevitable bust cycle, it will manifest itself in a single surviving concern – be it Hfx Shipyards, Seaspan, or Davie. No bets on whether it will be more than some infrastructure with a skeleton workforce. Most , if not all, of today’s players will go the way of St. John Shipbuilding and Drydock. It is simply a matter of time.

Its been said that the FREMM would be substantially cheaper than the CSC build. Further research would have revealed that on 24 February 2021, the Parliamentary Budget Officer released its report on the Canadian Surface Combatant’s latest estimated costs and made a comparison to the FREMM. It was estimated that buying 15 FREMM would cost us 71.1B and buying a mixed fleet of 13 FREMM and 3 CSC optimized for air defence would cost us estimated 71.9B. That is not substantially cheaper and much more than the 30 Billion quoted here.

Everything is more expensive in Canada thanks to unions. The government very well knew that these ships would be expensive, but the NSS was never about getting value for the dollar. The goals of the NSS are to build a strategic shipbuilding capability, provide employment and yes political gains. To get the yards to participate in the NSS, guarantees had to made to guarantee profit for the companies because of the schedule determined by the government. What they should have done was insist that yards be able to build multiple ships at a time or several different classes at a time such as what the UK is doing regarding the type 26. That is procurement for you in Canada, politics play into everything procured and Canada has demonstrated repeatedly their willingness to write a blank check to support Canadians building Canadian ships. I agree that it is less than desirable but even less desirable is no ships or something that can’t be easily modified or future proofed over decades like the CSC.

Additionally, there is a claim in the article that there would be no supply chain benefits using domestic suppliers. Like any builds of this type many of the combat systems are always bought offshore but there are plenty of domestic suppliers of equipment and some combat systems that are Canadian so yes there is certainly supply chain benefits to this build.

The 26.2 billion estimate in 2008 was merely a placeholder, as no one could predict what the statement of requirements was still be developed. Originally 3 air defence versions and 12 general purpose versions, eventually the GOC put all its eggs in the basket and decided it would 15 ships of the type 26 canadianized to do everything. Once that decision was made and capabilities chosen the price increased with additional increases because of the schedule the government made. The GOC estimates 7 years for the first but leveraging data from the BAE build and AUS may cut this down to 5 years. Once underway a new CSC every 19 months for the first 4 units and 12 months in between the rest. The decision for the UK to drop their planned purchase of the type 26 was an easy one to make because the UK operates a mixed fleet with different capabilities, Canada does not. It’s all of nothing for us, and rightly so. The government has been very clear that is no plan B.

Yes, the FREMM is a nice ship but well below the capabilities of the type 26. If we had chosen it and operated a mixed fleet which by the way comes with additional costs and risks and is fine for countries like the US which operates multiple classes of ships. Canada has been very clear that we would not do that

Yes, Fincantieri offered an unsolicited offer (it was not a bid) to build the FREMM for 30 billion. Of course, this was after they lost the competition and was seen to be a ploy (sour grapes perhaps) to try and stop the type 26 from winning. This “bid” did not contain any details and according to the PBO report in Feb would of cost over 70 billion. So no, it would not have saved 30 billion. The FREMM by all accounts is a very good ASW ship however the government of Canada has been very clear that all CSC will be equal in ASW and air defence. I have no doubt if Canada was at “Hook’em” we would have won with a Halifax Class.

I agree that the fleet is old but your plan to go with the last ship to commission is not sound. It should be the first ship to commission however more than likely it will the worse shape Halifax Class that will go first. The RCN and GOC is investing a lot of resources to keep the Halifax Class running and you must remember that crewing will be just as big a challenge as building them. FREMM may very well be a faster ship to build but why do you think that is so, the ship does not have the capabilities of the Type 26 and expected ship life of only 25 years compared to the CSC. This article should have been written a couple of years ago before the planning process started because your alternative currently does not hold any water. A change at this point would be incredibly costly and add years to build process, thankfully its going to happen.

A couple of points of clarification.

First, the SPY-6 radar has been under continuous development since at least 2013, when it was initially funded. As noted, it is only now being tested for certification onboard the Arleigh Burkes, and there have been reports of power and cooling issues for some time. So, while I am certain LM will eventually get the SPY-7 developed and certified, this will likely take many more years.

Second, the PBO was never tasked to explore the most cost-effective ways of procuring options to the CSC – it was handicapped by the assumption that any contender would have to built wholly in Canada. This is the fatal flaw in the NSS as it is currently structured.

Third, regarding the goal of building a self-sustaining Canadian shipbuilding industry, this cannot be achieved by subsidizing this industry. Nobody has yet demonstrated that Canada has, or will ever have, an international comparative advantage in warship construction. Moreover, I cannot see any export sales for a third-party warship design that is at least twice as expensive as available foreign designs. Therefore, if and when the CSC ever gets completed as planned circa 2050, what is to prevent the inevitable “bust” phase from taking place? Does this mean that Canadians have to further subsidize Canadian shipbuilders – all in the name of protecting sacrosanct jobs in Canada?

It will never be a self sustaining industry and I think everyone knows that. It is however a strategic capability that we can build our own ships rather than rely on a foreign entity, we have to pay the price for that. As for the bust, the whole idea is a continuous build cycle.

I guess if there were only one builder in Canada, and if that concern were given ALL the build work and carried each CCG and RCN project out in a consecutive manner, then that would technically satisfy the NSS ambition of having a domestic ship-building industry that was set up with a steady work order over the long term. Trouble is, executing consecutive programs would not re-capitalize the government fleets in anything close to a timely manner. Imagine waiting until all the icebreakers, fisheries vessels, and AORs were built before starting on CSC, or vice-versa.

The issue as I see it is that the government prioritized certain programs over others and the fact our relatively small shipyards can usually only build one project at a time. If we had things such as the UK and had several Type 26/CSCs going at the same time we would be in better stead. We simply left it too long.

WRT alternatives to CSC, my bet is that Canada will soldier on with the program in batches until a future government halts acquisition at, say 10-12 hulls, on cost grounds. Long before that the RCN will reconcile itself to the notion that it simply cannot recruit enough sailors for 15 CSC’s while also crewing the De Wolf class, the two AORs (Asterix being sold on to another navy), plus whatever submarine capability is hanging by a hawser thread.

This being the (likely) case, will someone explain to me the latest CSC graphic? Why does a ship of the tonnage of CSC carry only 24 Mk 41 cells? (Yes, I know there’s CAMM, although God knows why we need that AND Evolved Sea Sparrow!) If the RCN is astute it will build in deeper magazines now, and take the chance that they will be filled with something other than salt air. Better safe than sorry.

If not, forget about buying Tactical Tomahawk or another dedicated strike weapon. Devoting very limited magazine space to that would make so little difference to an allied coalition. See this piece by an Australian analyst:

https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/does-the-royal-australian-navy-need-tomahawk-missiles/

I think we will eventually get our 15 CSC, the rate of them being built gives the RCN plenty of time to recruit and train technicians as long as they don’t waste that time.

From what I can gather weight is the overriding cause of 24 vice 32 VLS.

On this CSC issue, I totally agree with you “Retired RCN”. It is all about saving tonnage and thus an issue of weight verses speed. My only issue is, why not still build them with 32 VLS cells but not fill the last 8 cells until needed for the future. (fitted for but not with).

The Aussie Hunter-class will have a 32-round launcher, so one wonders where the weight growth in the CSC came from. And since the latter are expected to perform AAW, a bigger launcher would seem to be essential.

Is the intent to distribute RIM-66s across a task group so the collective load meets or exceeds 32 rounds, and use co-operative engagement to deal with the air threat? Twenty-four cells housing a variety of missiles just doesn’t seem like a lot – especially if the RCN is serious about deploying a long-range strike weapon (i.e. Tomahawk) in sufficient quantity (best of luck on that). Even the 280-class had 29 cells.

Even for peacetime operations it’s gonna be REALLY expensive to arm these ships effectively. We can only wait with bated breath (or gritted teeth) for information on how many of each type of missile Canada will buy. One wonders to what extent the overall program costs are driven by this particular factor…

Totally agree BB. Also consider “IF” the government decides to get back into the BMD game, where is the room coming from for the SM3/SM6 missiles? IMO I have my doubts that taking away the extra silo of MK 41 VLS cells is going to contribute to any substantial speed increases for the CSC Frigates.

Hello Barnacle Bill. In my opinion, the more CSCs that are built, the costs will most likely decrease in time, so it will be more feasible to build all 15. The Halifax class has a crew of between 229-240 sailors on board for each deployment. If the CSC Frigate has a total crew of 204 sailors, that would seem to make it easier to crew all CSCs. The CAAM Sea Ceptor system is not a replacement for the ESSM but for the CIWS system with a longer range than the CIWS bullet vice the ExLS of CAAM with the extended magazine cells. Building deeper VLS canister cells would be prudent and the way to go and the RCN has probably considered that. That very well may happen, but who knows as the government or Lockheed Martin are not talking.

I’m no naval engineer, but I took a look at the systems on the Aquitaine class and compared them to those on the Hfx class after the HCM modernization. I then took into account pending upgrades to the Hfx’s underwater warfare capability. Aside from the SAM missile load, I don’t see much difference in capability between the Aquitaine and the fully-modernized Hfx. So, would we really be vaulting ourselves into the future with FREMM? Sure, we’d get a brand-new hull but what else? (Personally I don’t believe that we’d sail a combatant with only 120 crew members. Not much resilience there.)

If one compares the Aquitaine to the ship class(es) it replaced, then yes, the Marine national is embracing the next generation. But those older ships in French service (the Georges Leygues class) were no better than our un-upgraded Halifaxes. Thus by choosing FREMM to replace an upgraded Hfx, we’d be paying lots of money for only incremental improvements to our own capability.

I’d rather take the systems we’ve already paid for and graft them onto a new hull, as the Brits are doing with the Type 23->26 transition. Was this not contemplated as a way of 1) lowering the costs of the Hfx replacement, 2) reducing training costs while 3) speeding up delivery?

… with delivery of the {15th ship in 2045}…

This is a huge ‘error’. Canada’s Combat Ship Team states it will take (5 Years) just to build [1 Frigate].

[15 Frigates] x (5 Years Each) = {75 Years}

(2024)+{75 Years}= (2099)…

Bill Morgan, that’s not how ships are built. Shipyards do not wait until one ship is completely finished before starting the next one. In actuality, they start subsequent ships as soon as the previous ship has finished the “steps” required for a particular stage at the yard. So for the AOPVs, even though they do take around 4-5 years from start to finish, they’re able to deliver one every year because they start the second ship while the first ship is only ~one year into its construction.