By David Prior

There is growing awareness that the RCN requires Arctic-capable ships that can provide true logistical capability throughout the Arctic at any time of year. The USCG also recognizes this need for Arctic multifunctional security vessels. It was discussed at the 7 December 2022 House Transportation and Infrastructure's Subcommittee on the Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation hearing on the "U.S. Coast Guard’s Leadership on Arctic Safety, Security, and Environmental Responsibility."1 Requirements included multifunctionality (minutes 1:18:53 to 1:19:41) and oil spill mitigation (minutes 1:20:40 to 1:25:55).

Recently CBC presented information on the issue,2 which included a live interview3 with Vice-Admiral Angus Topshee, Commander of the RCN. In the CBC video, we hear of the need to protect Canada’s Arctic with Canadian naval ships equipped with amphibious capability. Assisting an Arctic community in distress in Canada’s far north was presented as one example of the non-military aid that such a vessel could provide. Sustained capability is essential; it requires an amphibious ship that can remain on station as an Arctic base for as long as the emergency requires, which could be many months. A naval amphibious assault ship is presented as a possible solution. Looking at a typical amphibious assault ship, the USS Iwo Jima, we see that they are big, boxy ‘cargo’ ships (minutes 1:00 to 1:32). That exceptional cargo-carrying capacity is ideal, indeed essential, for rendering assistance and sustaining remote communities.

Seaspan is offering to add amphibious capability to a standard Polar Max icebreaker, which is Polar Class 2 and thus fully capable of reaching anywhere in Canadian Arctic waters at any time of year (minutes 1:38 to 1:42). However, all conventional icebreakers, including the Polar Max, are not big, boxy cargo ships; they are powerful, sculpted, massive structures of steel crammed full of internal machinery and equipment. To use a land-based comparison, conventional icebreakers are massively powerful, very expensive and very complex bulldozers. However, the job of being a floating Arctic base requires a fleet of heavily armed, moderately priced, 18-wheelers, not a single very high cost, very attractive target which is all that Canada can afford. We can expect a single RCN Arctic amphibious armed icebreaker to cost $5 billion CAD. A non-militarized Polar Max is approximately $3.25 billion CAD.4 An American amphibious assault ship5 without polar capability costs approximately $3.28 billion CAD.

For the same $5 billion CAD, the RCN can have 12 (twelve) PMSVs6 (Polar Multifunctional Security Vessels) stationed at several DND bases across the Arctic. The current war in Ukraine has taught us that deploying a fleet of smaller, heavily armed vessels is a better strategy than deploying a single floating fortress, especially when the smaller vessels are heavily compartmentalized (like PMSVs) so that they are highly resistant to downflooding and more amenable to fire control7 in the event of a large missile or torpedo strike. A typical amphibious assault ship, built like a massive, thin-walled, floating warehouse with huge openings, has much in common with ocean ferries.8 With a fleet of economical PMSVs available, one of Canada’s conventional Polar Max and/or smaller conventional icebreakers escorts one or more PMSVs (which are truly amphibious, heavily armed floating bases) to the scene of the emergency, after which the icebreaker(s) can leave to perform other duties for which they were built. Meanwhile, the far less expensive and far more capable floating base(s), the PMSV(s), remain at the site of the emergency for as long as it takes.

A fleet of 8 PMSVs plays a role in this Canadian Arctic scenario.9

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eKITrB1j5Mg

- https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/navy-canada-arctic-defence-landing-ship-9.7027777

- https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/video/9.7028592

- https://www.davie.ca/en/news/2025-03-08-pm-announcement-en/

- https://hii.com/news/hii-awarded-contract-to-build-amphibious-assault-ship-lha-9/#:~:text=Construction%20on%20LHA%209%20is,the%20Navy%20and%20Marine%20Corps

- https://www.navalreview.ca/2022/12/the-case-for-a-polar-multifunctional-security-vessel/

- https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/2816283/navy-releases-extensive-bonhomme-richard-fire-report-major-fires-review/

- https://www.originalshipster.com/blog/archives/900; https://www.ukpandi.com/news-and-resources/safety-advice-training/article/articles/2022/the-capsizing-of-the-herald-of-free-enterprise/

- https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/programs/defence-ideas/element/contests/challenge/ideas-fictional-intelligence-contest-polar-paradigms-2045-defending-canada-sovereignty.html

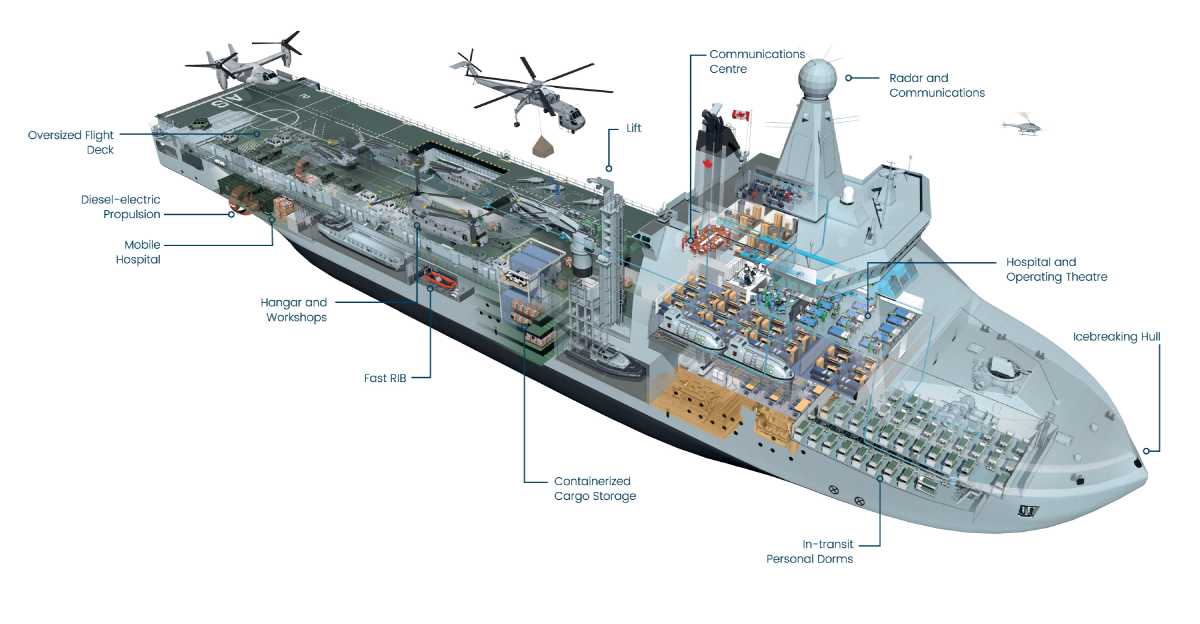

Image: The Global Logistics, Aviation, and Medical Support platform concept proposed by Davie includes an icebreaking hull for Arctic operations. Credit: Chantier Davie

19 thoughts on “RCN Polar Class 2 Amphibious Icebreaker”

Hello David. Your G-LAAM Polar Class 2 Amphibious Ice Breaker is a great start but in order for it to work within the RCN, you will have to give the vessel the size and power to at least match the new Canadian Polar Class 2 now being built by both Davie & Seaspan. It would at least have to have a Polar Class 2 Amphibious Capability to move a Canadian battalion strength with all its mechanical land capabilities. An ability to at least defend itself with a main gun with the ability to fire from at least ‘stand-off’ ranges and a decent AAW capability (possibly VLS SM2/NSM/Tomahawk/RAM & power enough for a laser weapon capability). It should also have a Command & Control System (CMS 330) with a Lockheed Martin SPY 7 V (3) OTH capability. A more than decent HA/DR capability will also be essential including LCVPs to ferry civilian personnel to & from the ship. Hospital capacity for all casualties should have enough space for at least 80-100 personnel with Operating rooms/CT/MRI Scans/Dental/Recovery Ward facilities. A Level 2 ashore hospital facility will be essential as well. Enough space for at least 2 Sqns of Helicopters.

Your G-LAAM concept seems to be on the right track but needs much more in order to be effective in the high Arctic. Enough space for Ship-A/C Fuel as well as space for UAV/UUV capabilities. Let’s not forget the number of RCN personnel, air crew and land personnel that would also have to be factored in and the training that will be required for all. The biggest factor would have to be power output. Enough power to move this ship to at least 25 kts with larger and more powerful diesel generators and bow thrusters. I would suspect this G-LAAM would have to be at least 1/3 larger than the CCG Polar Class 2 Icebreakers (Possibly over 30-35000 tonnes & well over 180 meters in length with a larger width & draft). And that’s just for one of these Amphibious Ice Breakers at a projected cost of between $4.5-5 Billion CAD in 2026 dollars. A minimum of at lease 3 of these ships will be required so it will not be cheap. My two cents worth. Cheers!

Your analysis of the proposed G-LAAM is highly accurate and confirms why G-LAAMs are the wrong choice for Canada, particularly in the Canadian Arctic. They are voracious money-pits and highly desirable targets. Unfortunately, by placing all of Canada’s ‘eggs’ in one mighty basket, all the Canadian eggs go down with the ship, taking with them Canadian taxpayers and perhaps Canadian Arctic sovereignty.

Hello again David. A recent ‘Ready-Aye-Ready’ RCN magazine article written in consort with the Navy’s top sailor Admiral Topshee, explains in detail why Canada needs a “Moveable Arctic Base” by conceptualizing a Canadian built, Polar Class 2 Amphibious Sealift Capability. This Canadian design seems to be just about what Canada needs for future Arctic operations. This capability is not just a “modest incremental evolution,” but a sorely needed priority for Canada in a rapidly changing geopolitical world now and in the long term. It is not just a nice-to-have capability, but rather an urgent priority for Canada now! The fact that Canada is strongly considering a Polar Class 2 Strategic Sea Lift Capability speaks volumes to a capability that is long overdue and a much-needed capability for us in the not-too-distant future. Canada is the only G7 country without an amphibious sea lift capability. Yes, Canada has flirted with this capability before, when France was willing to sell Canada the Mistral Class LHD for amphibious & HA/DR operations. There are other options on the market today including; The Spanish Juan Carlos LHD; The Italian Trieste Class LHA; The German Blohm Voss Class LHD design and of course the America Class LHA.

The problem with all of these LHD/LHA sealift vessel designs is that they all do not have an Arctic Polar Class 2 rating which means that this Canadian Amphibious Sealift Fleet has not been built…. yet. The Diefenbaker Class Polar Class 2 icebreaker now being built by both Davie & SeaSpan shipyards are the closest to what would be required for a Canadian amphibious sealift capability. This capability will not be cheap, however, and will probably be well over 30,000 + tonnes & over 180 meters long with a wider beam & deeper draft than what is now being built for the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG). A fleet of at least 4 of these Polar Class 2 amphibious sealift ships for sealift & HA/DR operations will be required. Based on the Polar Class 2 icebreakers being built now for the CCG, this ship can be built with Canadian ingenuity & know-how. With Canada quickly attaining its NATO goals of 2% of GDP this year & going to 5% of GDP by 2030, and with more trained personnel, this capability can happen, but may be a slow process. Forum members can read this article at https://readyayeready.com/ called “Canadian Navy Eyes Ice-Capable Amphibious Landing Ships for Arctic Defence”

This is not the first time Mr. Prior has advocated for PMSVs on this site, and it was a bad idea then for the same reasons it is a bad idea now: it substitutes an attractive paper fleet for the hard realities of Arctic access, lift, endurance, crewing, and basing. The Royal Canadian Navy has been explicit in recent media that this discussion is a thought exercise and anyone who follows Canadian defence planning knows exactly what that means: exploratory, unfunded, and far behind much larger priorities already straining the system. Regurgitating PMSVs as a supposed alternative to Polar Class logistics capability ignores physics and cost accounting alike; twelve hypothetical “cheap” vessels do not magically replace a year round PC2 hull, nor do they conjure ports, maintenance, crews, or sustained command and control in the High Arctic. Dressing this up with Ukraine analogies and “floating fortress” rhetoric doesn’t change the fundamentals: Canada’s Arctic problem is reach and staying power, not salvo density, and the RCN has far more urgent, real world capability gaps to close before indulging in another round of advocacy dressed as innovation.

Totally agree Richard with all of your responses to David Priors’ article. Even with a G-LAAM with Polar Class 2 capabilities, It will still not have the Amphibious Arctic capabilities the RCN requires. Nothing less than an LHA/LHD type vessel with at least Polar Class 2 capabilities will be required in order for the RCN to do the job required for amphibious & HA/DR duties. We already had our chance years ago when the French were willing to sell Canada the Mistral Class (but has no Polar Class designation) for amphibious & HA/DR, and we all know how that worked out. I still contend that the Spanish Juan Carlos LHD Class (if built to Polar Class 2 requirements) would be a much better option for the RCN. The training to evolve this amphibious capability will take a long time though. Just ask the Australian Navy. It took them over 20 years to develop their amphibious capability and they are still not quite there yet! The Juan Carlos LHD is roughly about 27,500 tonnes and with a PC 2 requirement, it would bring total weight well pass 30,000 tonnes alone not including ‘full load’ and could be built in Canada as well. Canada could never acquire 12 of these ships ($$) as Mr. Prior envisions, however a fleet of at least 3 Amphibious HA/DR LHD icebreakers will be an effective alternative and could work for the RCN and the CAF.

There is a lot of confusion in this commenting process. The G-LAAM with PC 2, illustrated at the beginning of the article, is now being slightly considered by the RCN. I am not recommending the G-LAAM with PC 2. I am recommending a fleet of 12 much smaller Polar Multifunctional Security Vessels (PMSVs) https://www.navalreview.ca/2022/12/the-case-for-a-polar-multifunctional-security-vessel/ https://www.navalreview.ca/2025/06/the-case-for-large-canadian-naval-vessels-built-with-modern-materials/

I agree with David Dunlop that the proposed ship, as illustrated above, is the wrong choice. It’s true that Canada could never afford 12 G-LAAMs or 12 Spanish Juan Carlos LHD Class (if built to Polar Class 2 requirements). Canada can afford only one of either. However, Canada can afford 12 PMSVs because 12 PMSVs cost the same as one of the the PC 2 suggestions. Reading the above links I provided in this comment will explain why this is so. Canada needs to occupy, not visit, the High North. PMSVs are the only credible way to do this, in part because they are multifunctional, economical, independent of southern bases, and useful on a daily basis. This is now what the USCG is finding desirable (reference link #1 in the article provides details). Importantly, PMSVs are far more valuable at enforcing sovereignty than toothless patrol vessels that cost twice as much, or unaffordable amphibious assault ships that cost 10X as much. PMSVs also do not require harbours with extensive infrastructure. All they require is natural shelter from storm waves and flowing pack ice. Wooden ships regularly over-wintered in the Arctic 300 years ago without massive concrete harbour infrastructure. PMSVs are floating bases, designed to disperse widely, which is what enforcing sovereignty needs.

There’s a persistent sleight of hand in the PMSV argument that keeps resurfacing on Broadsides, and it deserves to be addressed head on.

The claim is that a fleet of small Polar Multifunctional Security Vessels somehow offers a cheaper, more credible alternative to larger Arctic capable ships. That premise collapses the moment you move beyond notional diagrams and into real world naval operations. Twelve small hulls do not magically equal one large, capable platform once you factor in crewing, sustainment, training pipelines, command and control, maintenance cycles, ice damage repair, and logistics. Hull count is not presence if half the fleet is always unavailable, crew limited, or weather constrained. Canada has lived this reality repeatedly, including with the Kingston class, which were also sold as cheap, flexible, ‘good enough’ solutions.

The assertion that PMSVs can ‘occupy’ the Arctic rather than merely visit it is similarly misleading. Occupation is not achieved by scattering lightly supported ships across thousands of miles of austere coastline. It requires reliable logistics, medical support, aviation facilities, secure communications, ice management, and the ability to self sustain for long periods without heroic assumptions. A dispersed fleet of small vessels actually increases dependency on southern infrastructure, airlift and emergency support not reduces it. Over-wintering wooden ships 300 years ago is not a relevant benchmark for a modern navy operating under contemporary safety, environmental and personnel standards.

The claim that PMSVs avoid the need for ports and infrastructure is also overstated. Any vessel intended for continuous Arctic operations requires fuel resupply, maintenance access, crew rotation, waste handling and emergency repair capacity. ‘Natural shelter’ does not replace these requirements; it merely shifts risk onto crews and commanders. Designing ships around the assumption that they can safely loiter indefinitely in remote anchorages is not sovereignty enforcement, it is wishful thinking.

Cost comparisons are another recurring weakness. PMSVs are repeatedly framed as costing “the same as one PC2 ship,” but that arithmetic only works if you ignore the full life-cycle costs of twelve separate platforms. Twelve hulls mean twelve crews (or more), twelve maintenance burdens, twelve training streams, and twelve command problems. The RCN already struggles to crew and sustain its existing fleet. Proposing a dozen additional Arctic specialized vessels without a credible personnel or sustainment plan is not realism, it is denial.

Most importantly, PMSVs fail the sovereignty test they are supposed to pass. Sovereignty enforcement is not about constant low end visibility alone; it is about credible capability, resilience and response. A lightly built, lightly armed, lightly supported ship does not deter, reassure, or control anything beyond the most permissive environments. Presence without authority or endurance is symbolism, not strategy. Canada does not need more toothless platforms, especially ones optimized for idealized concepts of operations that collapse under pressure.

This is not the first time PMSVs have been advocated on Broadsides, and the flaws were evident then as they are now. Repackaging the idea does not fix the fundamentals. If Canada ever decides to ‘go all in’ on Arctic capability, the answer will not be a fleet of small, fragile compromises. It will be fewer, more capable ships aligned with real doctrine, real logistics and real people supported by deliberate investment in infrastructure, not arguments that pretend it isn’t necessary.

PMSVs are not a bold alternative. They are a familiar Canadian mistake, promising affordability, flexibility and presence, while quietly delivering none of them at scale.

A very large, year-round PC2 hull does not magically replace a fleet of smaller PMSV hulls that rely on widely available harbours (that are built in the coming decades) and icebreaker escorts. Like it or not, Canadian ports are coming to the Arctic, each of which will be quite capable of hosting a few thrifty and low-maintenance (epoxy composite hulls) PMSVs. Maintenance crews and sustained command and control in the High Arctic are also coming. Build a fleet of PMSVs, which provide exceptional redundancy plus logistics storage space, and fit with the future realities that are coming much faster now in a fast-changing, more dangerous world. Do not waste money building massive PC2 amphibious assault ships designed for beach invasions in southern waters. These do not require the RCN.

Your argument leans heavily on a future Arctic basing network that does not yet exist and treats that assumption as if it’s already a delivered capability. “Canadian ports are coming to the Arctic” may be directionally true over decades, but ports, fuel, maintenance, spares, housing, medical, comms, air access, and year-round sustainment are not a single checkbox nor are they guaranteed on the timelines implied here. If your concept of operations requires multiple new harbours plus permanent maintenance detachments plus “sustained command and control in the High Arctic,” then the fleet you’re really building is an Arctic logistics and shore infrastructure enterprise with ships attached not a ship program. Until that network is real, a flotilla of small hulls doesn’t buy resilience; it buys more mouths to feed, more crews to generate, more rotations to manage, and more things that break far from help.

The second sleight of hand is the quiet reliance on icebreaker escorts as if they are an inexhaustible utility service. Escort demand is exactly the bottleneck in winter and shoulder seasons; building a fleet whose year-round access depends on another scarce fleet is not “redundancy,” it’s coupling and coupling is fragility. Add to that the hand wave about “epoxy composite hulls” in the Arctic: composites can be excellent in the right roles, but ice loads, repairability in austere conditions, and the practical reality of damage control and field repairs at high latitude are not solved by material optimism. A “thrifty, low maintenance” patrol vessel becomes a very expensive liability the moment it meets real ice, real weather, or real operational tempo without a mature support ecosystem.

And finally, the strawman: nobody serious is arguing for “massive PC2 amphibious assault ships designed for beach invasions in southern waters.” That’s a rhetorical flourish, not a requirement. The real debate is whether Canada needs true Arctic logistics the ability to move fuel, stores and capability when and where the Arctic denies you harbours, escorts, or good fortune. If you accept that the environment is the adversary half the time, then you plan for access and sustainment first, not for the most optimistic interpretation of “ports are coming.”

A more grounded answer is a mixed fleet: modest numbers of smaller, affordable hulls for presence and constabulary work where infrastructure exists (or in the navigable season), paired with a small number of high-end, ice-capable support platforms that can actually move the needle when the map turns white and the weather closes the door. In other words: don’t bet the concept on “coming soon” ports and borrowed escorts; buy the minimum credible ability to sustain operations when those assumptions fail. That isn’t “magic PC2,” and it isn’t “PMSVs everywhere,” it’s designing a force that works in the Arctic we have, not the Arctic we hope gets built.

Thank you for supporting my argument in favour of PMSVs (reference #6 in my article). PMSVs are mobile floating bases, modest in size and very low in maintenance requirements. They do not require extensive shore logistics. Even bottom painting is optional. The main feature required by a PMSV harbour is natural protection from the forces of nature. PMSVs won’t start arriving until 2035, just in time for a few very basic harbours to be completed. Nanisivik is likely to be completed sufficiently for the arrival of several PMSVs https://www.navalreview.ca/2025/02/the-nanisivik-naval-facility/ . The world is moving fast these days. I am assuming that Canada today can rise to this very doable challenge. It’s likely that, in 10-15 years, Canadian recruitment will be more successful that we have seen in the past. Because new naval vessels take so long to develop and start building, we cannot afford to wait until launch day to start looking for new crew. If we multitask, we can start work at the same time on both challenges.

PMSVs will need icebreaker escorts if they have somewhere essential to go in the winter months. Such trips will likely be rare, and the ice-free season of navigation is lengthening (we are planning for 2035 and beyond). By then we can expect there will be more icebreakers working in the region. The bottlenecks will be smaller and fewer. Utilizing icebreaker capacity only when necessary is for more economical than dragging around thousands of tonnes of extra capability all the time for the life of the vessel. I have dealt with the “reality of damage control and field repairs at high latitudes” in previous comments. As for epoxy composite hulls in high latitudes, talk to the Russians https://www.navalreview.ca/2025/06/the-case-for-large-canadian-naval-vessels-built-with-modern-materials/ . I have dealt with “repairability in austere conditions, and the practical reality of damage control and field repairs at high latitude” in previous comments. No problems there.

This comment by you is exactly correct: “The real debate is whether Canada needs true Arctic logistics the ability to move fuel, stores and capability when and where the Arctic denies you harbours, escorts, or good fortune. If you accept that the environment is the adversary half the time, then you plan for access and sustainment first,..”. All these are reasons why PMSVs are essential.

“PMSVs everywhere” are the “modest numbers of smaller, affordable hulls for presence and constabulary work” that you correctly say are required. Elaborate infrastructure and maintenance not required for PMSVs. Far more is required of Canadian polar naval vessels than constabulary work; they need powerful teeth, which PMSVs have (details in the reference links). PMSVs are the “ice-capable support platforms that can actually move the needle when the map turns white and the weather closes the door.” They can comfortably and economically live year-round in the Arctic performing multiple tasks, both civilian and military, even when icebound (eyes & ears, heliports, medical services etc). They operate two Arctic helicopters so can provide that capability. They only require icebreaker escort when a transit is required in winter months, a relatively rare occurrence. By 2035, there will be more icebreakers available. Ports suitable for most of a PMSV’s requirements already exist throughout the Arctic; they are nature’s safe harbours.

David, I think this response neatly illustrates where the PMSV argument continues to over-promise and under-acknowledge operational reality.

First, the assumption that PMSVs can function as “mobile floating bases” with minimal logistics and optional maintenance is not credible for year-round Arctic naval operations. Bottom painting is not optional for vessels intended to loiter in cold, fouled waters for years at a time, and neither is routine hull, propulsion and systems maintenance. Even composite or epoxy hulls do not eliminate corrosion, fatigue, mechanical wear, or the need for skilled technicians, spares, dry access, and environmental controls. Natural harbours do not replace workshops, cranes, power, fuel handling, secure communications, or medical evacuation pathways. The Arctic punishes deferred maintenance harder, not less.

Second, the repeated reliance on future conditions, better recruitment, more icebreakers, more infrastructure, longer ice-free seasons does not strengthen the case; it weakens it. Defence capability must be designed around assured access, not optimistic forecasts. Planning a fleet that assumes icebreaker availability for essential winter transits is the opposite of resilience. Icebreakers are scarce, multi-tasked, weather-limited assets; tying routine naval mobility to their availability creates single point of failure, not economy. Designing ships that require escort to move when conditions worsen concedes the environment to the adversary rather than mastering it.

Third, PMSVs do not resolve the core issue you correctly identify but then misapply: true Arctic logistics. Logistics means moving fuel, stores, personnel and capability when ports, escorts and luck are absent. A constellation of small hulls dependent on escorts and benign conditions does not provide that. Fewer, more capable polar vessels with organic ice performance, endurance, lift and sustainment do. That is why polar operators globally converge on larger, more capable hulls despite higher unit cost: they replace uncertainty with control.

Finally, describing PMSVs as having “powerful teeth” while also portraying them as low maintenance, minimally supported, and economically crewed platforms is internally inconsistent. Combat systems, aviation facilities, sensors and command spaces all drive complexity, crewing, training burden and sustainment demand. You cannot simultaneously minimize infrastructure and maximize capability without paying that bill somewhere, usually in availability and readiness.

The debate is not about whether presence matters, it does. The question is whether Canada should meet that requirement with a fragile web of optimistic assumptions, or with fewer, harder, more self reliant ships designed to operate when the Arctic does what it does best: deny access, degrade systems and expose wishful thinking.

Hello Richard,. Where do I begin. A Canadian Arctic Polar Class 2 Amphibious Sea Lift Capability is not a “modest incremental evolution” as you say, but a sorely needed priority that Canada requires in a rapidly changing geopolitical world now and in the long term. It is not a ‘nice to have’ capability, but rather an urgent priority for Canada right now! The fact that Canada is strongly considering a Polar Class 2 Strategic Sea Lift Capability speaks volumes to a capability that is long overdue and I believe will be a much-needed capability for Canada in the not-too-distant future. Canada is the only G7 country without an amphibious sea lift capability. Yes, Canada has flirted with this capability before with the French Mistral Class LHD but there are other options as well including; The Spanish Juan Carlos LHD; The Italian Trieste Class LHA; The German Blohm Voss Class LHD design and the America Class LHA. In 2024 I wrote an Article for the Canadian Naval Review called “A Strategic Canadian Amphibious Sealift Capability in CNR Vol. 13-4. It can be viewed at: https://www.navalreview.ca/wp-content/uploads/CNR_pdf_full/cnr_vol13_4.pdf.

The problem with all of these LHD/LHA Sealift vessel designs is that they all do not have an Arctic Polar Class 2 rating which means that this Canadian Amphibious Sealift Capability has not been built….yet. The Diefenbaker Class Polar Class 2 now being built by both Davie & SeaSpan shipyards are the closest to what would be required for a Canadian amphibious sealift capability. This capability will not be cheap and will probably be well over 30,000 + tonnes & over 180 meters long with a wider beam & deeper draft than what is now being built for the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG). A fleet of at least 4 of these Polar Class 2 amphibious sealift ships for sealift operations and Humanitarian Assistance & Disaster Relief (HA/DR) will be required. Based on the Polar Class 2 Ice Breakers being built now, this ship can be built with Canadian ingenuity & know-how. With Canada quickly attaining its NATO goals of 2% of GDP this year & going to 5% of GDP by 2030, with more trained personnel, this capability will happen. It took Australia however over 20 years to gain this capability so it will be a slow process.

David, appreciate the thoughtful and detailed reply but I still think you’re leaping several steps ahead of both Canada’s actual needs and its capacity to absorb a capability of this scale at this time.

Where we fundamentally diverge is on urgency. A Polar Class 2 amphibious sealift fleet is not a modest evolution of existing capabilities, but a fundamental change in doctrine, force structure, basing, crewing, sustainment, and political intent. That matters, because Canada does not currently have the missions, concepts of operations, or trained force generation pipelines to justify treating this as a near term priority. Calling it “urgent” does not make it so. The Arctic security challenge Canada faces today is overwhelmingly about presence, logistics, surveillance, sovereignty enforcement, and resilience, not forcible entry or large scale over the shore lift.

The G7 comparison is also misleading. Most G7 amphibious fleets exist to support expeditionary power projection alongside allies, not homeland defence. Canada has deliberately chosen a different strategic posture for decades, emphasizing alliance contribution through high end niche capabilities (ASW, escorts, MCM, command roles) rather than duplicating US, UK, French, or Italian amphibious mass. Being “the only G7 without LHDs” is not evidence of a gap, it’s evidence of a different division of labour within NATO.

You are absolutely right that existing LHD/LHA designs (Mistral, Juan Carlos I, Trieste, America class, etc.) are not Arctic PC2-rated, and retrofitting them into that space would be eye wateringly expensive. But that cuts against your own argument. A 30,000–40,000-tonne PC2 amphibious ship is not a natural derivative of the Diefenbaker icebreaker program, it would be a bespoke, first of class design with enormous technical, schedule, and cost risk. We already struggle to crew, maintain, and deploy far smaller fleets. Adding four PC2 LHD scale ships would come at the direct expense of escort availability, submarine regeneration, MCM renewal, and Arctic infrastructure ashore.

HA/DR is often cited here, but Canada already conducts HA/DR effectively using airlift, AOPS, MSC-style chartered shipping, Berlin-class when finished and allied sealift, without needing an Arctic-rated assault ship. A PC2 LHD would spend the vast majority of its life doing tasks that do not require PC2 or an amphibious well deck, an extraordinarily expensive way to solve a niche problem.

Finally, the funding argument assumes away the hardest part. Even if Canada reaches 2% (or more), money does not instantly generate trained crews, aviation detachments, amphibious doctrine, joint command structures, or sustainment capacity. Australia’s 20-year journey is not a reassurance, it’s a warning. Australia made that investment because amphibious operations sit at the core of its regional strategy. They are not peripheral.

If Canada ever decides to go all in on Arctic sealift, a commercial-off-the-shelf-based logistics ship with ice strengthening, stern ramp, heavy cranes, modular accommodation, and Mexeflote-style connectors would deliver 80% of the practical benefit at a fraction of the cost and institutional disruption, without pretending we need Arctic assault ships today.

So yes, interesting, worth studying, and perhaps viable in the very long term. But calling a PC2 amphibious fleet an urgent national priority right now simply does not align with Canada’s actual threat environment, force structure, or readiness realities.

Richard. I am not arguing for any one of these LHAs/LHDs but for a larger made in Canada design based on the CCG Diefenbaker Polar Class 2 design. I do believe though that your thoughts are mis-aligned with the realities of what is happening now in this new geopolitical world.

The current war in Ukraine has taught the world that, today, a massive, and massively expensive, weapon can be defeated by a swarm of less capable but still adequate weapons. An amphibious assault vessel like the above amphibious icebreaker might be quickly dispatched by the first swarm of 100 submarine-launched, AI-guided drones attacking its bridge windows with high explosives, probably followed within seconds by drones entering the interior and destroying the bridge, control and communications centres. Tiny drones packing a powerful punch can now go almost anywhere inside a structure. In twenty years or less, it will no longer be “almost”. Old-fashioned ships like the above amphibious icebreaker will be the first to go when the shooting starts. Also first to go will be the light armament on the vessel, swiftly removed by drones or AI-guided missiles https://x.com/NavalInstitute/status/1784753615267131809 (28 shells just to sink a small fishing vessel).

Richard Bungay expresses unsubstantiated concerns about the PMSVs. The answers to all his concerns can be found in everything I have presented on PMSVs in the Canadian Naval Review (don’t forget the references). A re-read may clarify the details. Mr Bungay presents information on Canada’s Kingston class ships, calling them “cheap, flexible, ‘good enough’ solutions”. And so they were. Every good ship design strives to meet the assigned objectives (to be good enough) and to be economical to build and operate (not “gold-plated”). Gold plating is not the same as armour plating. The Kingston class design appears to have met the objectives assigned to it at the time: “The Legacy of the Kingston Class” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hbUIPdmXTeo. Comparing a PMSV (100m LOA and 4000 tonnes) to a Kingston class vessel (55.3m LOA and 970 tonnes) is inaccurate. There’s a noticeable difference both in dimensions and Arctic endurance. Much greater endurance means much longer Arctic patrols without the need for base support (crew changes etc). Arctic patrols will be many months longer than Maritime patrols. PMSVs are designed for that reality.

Mr Bungay is absolutely correct when he states that ” A lightly built, lightly armed, lightly supported ship does not deter, reassure, or control anything beyond the most permissive environments”. While most of his statement applies to AOPS, none applies to PMSVs, which are very heavily armed for close proximity fighting and the projection of both lethal and non-lethal force. This simple, low-cost, rugged, reliable Arctic-friendly force technology does not require the massive arrays of delicate and highly expensive electronics needed for the very long-range weapons on fighter aircraft, frigates and destroyers. Traditional short-range naval weapons are useful for firing warning shots but little more (28 shells to sink a medium-size fishing boat https://x.com/NavalInstitute/status/1784753615267131809 ).

PMSVs cannot avoid the need for Arctic ports and infrastructure but they are far less reliant on them than any other naval surface vessel. The ports can be quite basic to meet the needs of PMSVs. The PMSV’s unique features offer exceptional endurance. While it’s true that any vessel intended for continuous Arctic operations requires fuel resupply, maintenance access, crew rotation, waste handling and emergency repair capacity, the PMSV requires far less of all of them. The reasons why have already been published in the Canadian Naval Review, usually in the references. PMSVs cannot safely loiter indefinitely in remote anchorages, but they don’t have to. As for PMSVs being “small, fragile compromises”, 4000 tonnes is not particularly small; regarding fragility, the Russians would be the experts to talk to. They are deploying a fleet of 40 composite warships, including to a war zone (Black Sea) and the Arctic https://www.arctictoday.com/few-months-after-ukrainians-sabotaged-sister-vessel-new-russian-minesweepers-prepare-to-sail-to-arctic-base/ https://www.kchf.ru/eng/ship/minewarfare/vladimir_emelyanov.htm https://maritime-executive.com/article/russia-readies-world-s-largest-monolithic-fiberglass-ship .

I appreciate the time and effort you have put into developing the PMSV concept, and I have read your contributions on the subject. However, repeatedly asserting that “the answers are already published” is not a substitute for engaging with the specific concerns being raised. If a concept cannot withstand direct scrutiny without referring readers back to earlier work, that in itself should invite reflection.

On the comparison with the Kingston class: I am not arguing that PMSVs and Kingstons are equivalent platforms. The comparison was made deliberately to illustrate a design philosophy, not a displacement figure. The Kingston class succeeded because it was aligned with a clearly defined mission set, institutional capacity, and sustainment reality. Size alone does not confer relevance, deterrence, or survivability. A larger hull that is still lightly defended, lightly supported, and dependent on permissive conditions does not escape the fundamental limitations that applied to earlier “good enough” solutions.

Endurance is being treated here as a proxy for control, and that is a critical leap. Longer patrols do not equate to deterrence or reassurance in a contested or escalatory environment. Presence without the ability to impose consequences, manage escalation, or survive first contact is not control; it is visibility. Arctic operations magnify this problem rather than solve it, because isolation, limited reinforcement, and long response times increase the penalty for miscalculation.

The claim that PMSVs are “very heavily armed for close proximity fighting” raises more questions than it answers. Modern maritime security is not decided by short range gunnery exchanges. Deterrence and control rest on sensor reach, command and control, integration with joint and allied systems, layered self defence, and the ability to operate credibly across the escalation spectrum. A platform optimised for close in engagements is, by definition, one that has already failed to shape events at range. Designing ships around the assumption that close quarters combat is acceptable or likely is not a virtue; it is an admission of strategic failure.

Similarly, dismissing modern combat systems as “delicate and expensive electronics” misunderstands why they exist. They are not luxuries; they are what allow naval forces to avoid fighting at knife range in the first place. Removing those systems does not make a ship rugged or economical in any meaningful operational sense; it simply transfers risk from technology to sailors and replaces deterrence with hope.

On infrastructure, we are largely in agreement on the facts and diverge on the implications. Yes, PMSVs may require less support than some larger surface combatants, but “less” is not the same as “little,” and it is certainly not “optional.” Fuel, maintenance, crew rotation, waste handling, emergency repair, and medical support remain non negotiable realities for any vessel intended to operate continuously in the Arctic. This is a system of systems problem, not a hull design problem, and no single ship concept can wish that away.

Finally, citing Russian composite hulled vessels as evidence of robustness conflates fundamentally different missions, operational contexts, and risk tolerances. Mine countermeasure vessels operating under layered defences and within an authoritarian command culture are not a valid analogue for Canadian sovereign presence, crisis management, or escalation control. Canada does not design naval forces on the assumption that losses are acceptable, nor should it.

At bottom, the PMSV concept relies on a series of substitutions: endurance in place of deterrence, presence in place of control, simplicity in place of survivability, and confidence in place of strategy. These substitutions may appear attractive on paper, but they collapse under real world scrutiny. A ship that can remain on station for months yet cannot credibly shape behaviour, survive escalation, or integrate into a modern joint force is not a solution to Arctic security, it is a persistence experiment masquerading as strategy.

You present many comments on issues which have previously been addressed. Regarding your knife fight scenario, sea confrontations at close quarters are still with us. They appear regularly in the widely available news these days. A fully equipped navy has the tools to deal with them, but today none do. Such basic tools are now out of fashion, but the need still exists. To paraphrase, never bring fragile ships that are greyhounds of the sea, armed only with long-range missiles and sophisticated electronics, to a brawl akin to a knife fight. A navy with both powerful long range plus powerful very close range capabilities is more potent, just as a modern city fire department with both ladder trucks and ground level pumper trucks is more effective. This article provides details on the issue which will answer your concerns https://www.navalreview.ca/2022/12/the-case-for-a-polar-multifunctional-security-vessel/ .

PMSVs in the Arctic was a unsound idea then and is still an unwise idea now. I can be sure that the RCN and Canada won’t ever do such a thing. To go to the Arctic we have AOPVs and in time ice-capable continental Corvettes. Honestly talking about it further is a waste of time.