By Dan Middlemiss, 20 January 2024

Most of you will recall that David Pugliese reported that DND had pledged to provide a current update for CSC costs by the end of 2023.[1] He noted that DND stated that the new costing update would cover the specific build estimate for the first 3 ships. In addition, DND would provide a cost estimate model update for the total 15-ship program and this would include material and labour, contractor program management, integration engineering, the technical data package as well as training, and also the costs of weapons, but not the recurring costs of spare parts and ammunition.

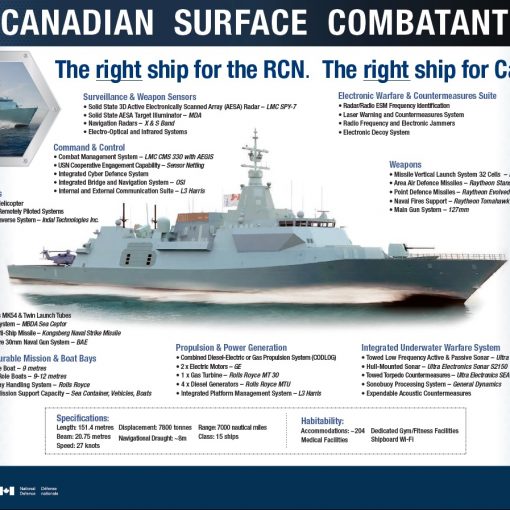

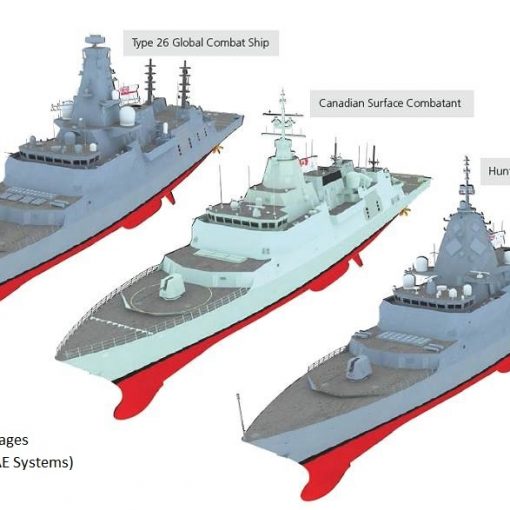

Pugliese contended that this update will focus public attention on Ottawa’s longstanding claim that it has the program well under control and that the total CSC project costs will not exceed $56-60 billion. The government has remained firm in this conviction despite the much higher cost projections provided by the Parliamentary Budget Officer. So it would appear that DND and Public Services and Procurement Canada have a lot at stake regarding the accuracy of their cost estimates and public perceptions of their overall management control of the CSC project. Moreover, critics of DND’s selection of a ‘Canadianized’ variant of the British Type-26 frigate will be quick to compare the new cost estimate with the costs of roughly comparable warships being built in foreign shipyards.

Here are a few observations about what we might expect when this update is finally released to the public.

It is almost certain that there will be some confusion as to what exactly will be included in a ‘build’ estimate. Terms like ‘sail-away cost,’ ‘unit procurement cost,’ ‘production cost,’ ‘initial spares,’ ‘program acquisition cost,’ ‘project cost’ and ‘life-cycle cost’ are frequently bandied about with little clarity or consistency in use.

To assist us in making sense of this confusing terminology, there are a variety of sources available. In principle, perhaps the most useful should be the Allied Naval Engineering Publication (ANEP)-41 which has gone through a number of revisions over the years.[2] However, like most NATO attempts at standardization, this publication is not used consistently by all NATO members, including Canada. But its list of commonly used costing terms is certainly a good starting point. For those who have trouble finding this document, consult Eric Lerhe’s brief summary of the three main ship costing terms used in ANEP-41.[3]

Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Officer has discussed its own organization’s costing methodology for the CSC in several updates, with its latest outlining what the PBO includes in its ‘acquisition production costs.’[4] For an interesting discussion of the very close similarity in DND/Ottawa and PBO cost estimates, see the Defence Deconstructed podcast, “Costing CSC,” (26 February 2021) between David Perry and Yves Giroux, Canada’s PBO.[5]

In the United States, the Congressional Budget Office has published an informative resource on its own warship costing methodology.[6]

We should note that most of these sources deal with costing terminology and what items should or should not be counted under each of the definitions. However, complications arise in the real world of warship costing when it comes to actually estimating the value of certain of the key costing variables, particularly those in the distant future, where great uncertainties are sure to exist.

For example, a key factor will be the rate of inflation in the specialized world of advanced warship technology. Based on well-documented examples, we know that even slight variations in the projected inflation rates in the shipbuilding sector – which often significantly exceed the rate of inflation for consumer goods and services as measured by the Consumer Price Index – can have a large impact on forecast warship costs. DND used to make available the defence inflation rates for various items in its annual Economic Model. However, this model fell into disuse when DND stopped trying to inflation-proof its military procurements under the formula funding arrangements that were in place in the 1970s and 1980s. Canadians can still acquire a version of this Economic Model under the Access To Information Act, but this approach is not recommended for the impatient or faint-hearted among us.

So we should be careful to note the projected rates of inflation that might be attached to the forthcoming CSC costing update. The impact of inflation on naval shipbuilding costs is relentless, and can have a significant impact on even a limited batch production run of 3 ships. Just what this impact might be depends on the planned construction tempo for ships in a given batch (e.g. will there be one ship built every1.5-2 years?), and even more so on what the anticipated gap will be between production batches. There is room for much uncertainty regarding the latter because a lot will depend on what future governments decide. Political considerations are notoriously difficult to predict let alone to try to quantify.

In addition, government agencies tend to be far more optimistic than, say, the Governor of the Bank of Canada in predicting low rates of future inflation. After all, they have to display confidence in the government’s ability to manage the economy in a fiscally responsible manner.

Another important factor to watch for are DND’s estimates of the possible shipbuilding ‘learning curves’ for the CSC. Such ‘learning’ involves not only workers learning how to do their jobs more efficiently over time, but also to what extent the shipyard can learn to innovate and to inject more efficient techniques and processes into building the CSC, again over time. If such learning curves are substantial, then so too will there be substantial cost savings in ship construction.

Good sources concerning these factors, as well as others, can be found in the now classic RAND study[7], and also in two useful articles by David Peer about rising costs and scheduling issues in Canadian naval shipbuilding.[8] These provide evidence that the real world of warship shipbuilding is filled with many uncertainties and practical difficulties than most cost estimators imagine.

This brief overview is necessarily incomplete and perhaps a bit simplistic. Nevertheless, I hope it will prove to be a solid starting point for those of us who want to understand DND’s CSC costing update when it is released.

Notes

[1]. David Pugliese, “Canadian Surface Combatant: New Cost Estimates Due This Fall,” Esprit de Corps, 30:7, 8-10. [Accessed at: https://fliphtml5.com/insrc/wlio]

[2]. See for example, NATO, ANEP-41, (Edition 4), “Ship Costing” (NATO Standardization Agency, April 2006), pp. 4-5 and 4-6, and especially the Appendix A, “NATO Ship Cost Terms and Definitions,” pp. A-2 to A-29.

[3]. Eric Lerhe, “Fleet-Replacement and the ‘Build-at-Home’ Premium: Is It Too Expensive to Build Warships in Canada?” Vimy Paper No. 32 (Ottawa, ON: Conference of Defence Associations Institute, July 2016), pp. 4-5. [https://cdainstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Vimy_Paper_32.pdf]

[4]. Canada, Parliamentary Budget Officer, “The Life Cycle Cost of the Canadian Surface Combatants: A Fiscal Analysis,” 27 October 2022, p. 8. [https://distribution-a617274656661637473.pbo-dpb.ca/747dfffc97de30adc19e38143f28b6e8334a0f7510c5c3a94c465a41c66cf504]

[5]. Accessed at: https://www.cgai.ca/costing_csc

[6]. US, Congressional Budget Office, “How CBO Estimates the Cost of New Ships,” 27 April 2018. [https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/53785-cost-estimates-new-ships.pdf]

[7]. Mark V. Arena, et al., “Why has the Cost of Navy Ships Risen?: A Macroscopic Examination of the Trends in U.S. Naval Ship Costs Over the Past Several Decades” (Santa Monica, RAND Corporation, RAND Report MG 484, 20 April 2006). [https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG484.html]

[8]. See, David Peer, “Estimating the Cost of Naval Ships,” Canadian Naval Review, 8:2, (Summer 2012), pp. 4-8. And, David Peer, “Realistic Timeframes for Designing and Building Ships,” Canadian Naval Review 9:1, (Spring 2013), 4-9.