By Dr. Dan Middlemiss, 15 November 2021

Earlier this month, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) published a Special Report dealing with Australia’s equivalent of Canada’s National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS).1 This Report by Dr. Marcus Hellyer, ASPI’s experienced Senior Analyst, touched upon many aspects of Australia’s two major naval procurement programs, but its findings should resonate here in Canada.

Hellyer’s central argument is that Australia’s two major naval procurement programs, the Hunter-class frigate and the nuclear-powered submarine, are progressing far too slowly. The first frigate is scheduled for delivery in 2033, and at best, the initial nuclear submarine will not be delivered before the late 2030s. This, coupled with evidence that the Hunter-class frigates will be built with a very minimal 32 vertical launch systems (VLS), have only a bare minimum of land-attack missiles, will be overly heavy and underpowered, and will possess only the tiniest margins for future growth, will leave the Australian Navy with a serious capability gap over the next 20 years. These twin shortcomings require immediate hedging measures to forestall a dangerous situation developing.

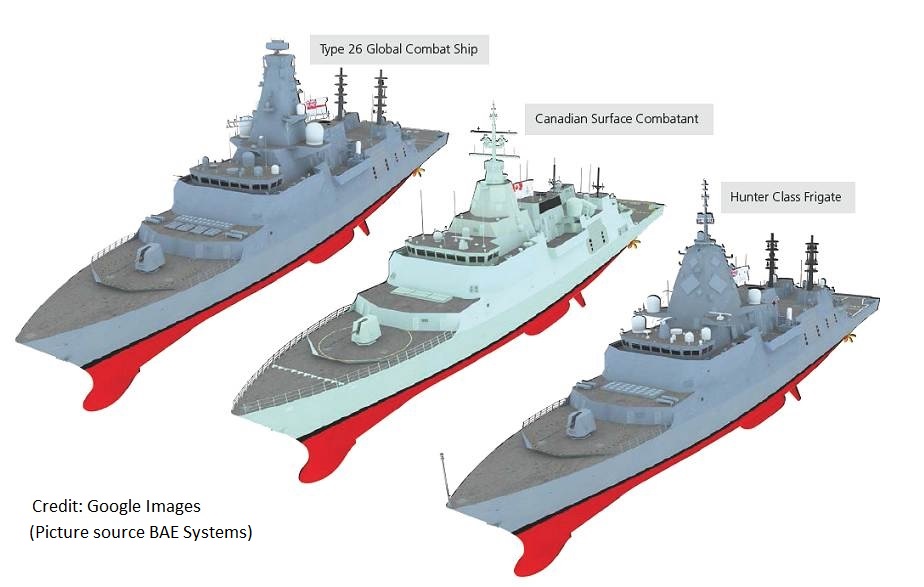

Hellyer’s analysis bears striking similarities with the current situation in Canada. Thus far, Ottawa does not expect a construction contract for its equivalent of the Australian and British Type-26 frigates, the Canadian Surface Combatant (CSC), to be concluded before late 2023-24, with the first warship being delivered no earlier than 2031 or perhaps later. Furthermore, Jeffery Collins has discovered an Access to Information briefing note urging the Department of National Defence (DND) to “kick off without delay” a replacement plan for Canada’s 4 Victoria-class submarines or else face what Collins depicts as a defence gap in the arctic.2

To state that planning for Canada’s CSC lacks urgency is to grossly understate the obvious. Such plans first began in earnest in 2008, and the intent was to deliver the first frigate in 2020.3 Almost at once this overly optimistic target was slipped to 2025, and the estimate now is for the first of this class to be delivered in the early 2030s.

As Hellyer notes of the Hunter-class, “wishful thinking has reigned” in the Australian fast frigate program, its schedule has been “moribund,” and costs have increased to the point that the total number to be built is in question. The Australian government has decided “to choose the least mature design and then to perform fundamental modifications to it.” The result has been “instability in the reference ship’s design” and a weight growth from about 8,800 tonnes to over 10,000 tonnes. He notes that there will be challenges to integrate the various systems, and all this will add to prospect of further schedule delays and the injection of “additional risk into the program.”4

Tellingly, Hellyer notes that the Hunter-class, when it finally materializes, will be slow, possess an inadequate number of VLS at 32, carry only 8 maritime-strike missiles, and will have only a 2.5 percent future growth margin.5

Of course, it is difficult to compare the Australian Hunter-class to Canada’s CSC, because in the latter case, we have no firm contractual information because there will be no contract for several years. But similarities to the Australian case abound.

Canada, too, picked the least mature frigate design and has evidently modified the original reference ship design extensively. There will certainly be challenges in integrating several new sensor, communications, and weapons systems from the UK, the US, and from Canada. The original design has increased from around 5,500 tonnes to approximately 9,400 tonnes. We do not know what design margin will be available for future growth, but the Hunter-class data provide a cautionary tale. As Hellyer alludes, unless the basic principles of hydrodynamics have magically changed, the power required to propel a 9,400 tonne ship at a given speed will be much more than that required for a 5,500 tonne ship, yet the proposed UK power plant remains the same. Mikael Perron argues that, while the current power is adequate for a 7,800 tonne CSC, if the full displacement weight is actually 9,400 tonnes, “(T)hat would be a totally different game.”6

The CSC will also feature only 32 VLS – at the low-end for most current frigates, and will be fitted for but not with Tomahawk land-attack missiles. Finally, and indisputably, Canada’s CSC is certain to eclipse Hellyer’s claim about the Hunter-class: “Overall, of all contemporary warships, it seems to be the most expensive for getting missiles to sea.”7

Space limitations prevent a discussion of Hellyer’s proposed solution to the naval capability gap in Australia. However, it remains clear that without a vigorous sea change in approach to both Canada’s CSC and submarine procurement programs, Canada will be left to face 21st century threats with increasingly obsolescent technology.

Notes:

1. Dr. Marcus Hellyer, “Delivering a stronger Navy, faster”, Special Report 177, (Barton, Australia: November 2021). Accessed at: https://www.aspi.org.au/report/delivering-stronger-navy-faster

2. Jeffrey F. Collins, “Without plan for new submarines Canada faces defence gap in the Arctic”, Financial Post (8 November 2021). Accessed at: https://nationalpost.com/opinion/jeffrey-f-collins-without-plan-for-new-submarines-canada-faces-defence-gap-in-the-arctic

3. Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services), DND, “Audit of the Canadian Surface Combatant Project”, (November 2015), iii-iv.

4. Hellyer, 7-9.

5. Hellyer, 13.

6. Mikael Perron, “Long-term Operations and Sustainment Costs for the CSC”, Canadian Naval Review, 17:1 (2021), 32.

7. Hellyer, 13.

7 thoughts on “Analysis of Australia’s Naval Shipbuilding Programs: Some Possible Implications for Canada”

I believe even the minimum number of 32 MK 41 VLS Canisters is now in jeopardy. With the latest CSC Frigate graphics from LM, we only see 24 VLS Canisters forward, so even the “fitted for but not with” scenario seems to be in doubt. Of course we don’t know because of the “secrecy” from the government…..again. The only way now to maximize speeds of 30+knts for the CSC Frigate would seem to be fit 2 x RR MT 30 gas turbines but don’t know if even that is feasible at this point.

Building at least 3 more Hobart 11 AAW Destroyers at first brush seems to make a lot of sense giving that the ADF is in the same “pickle” with the Hunter class as Canada is with the CSC Type 26 Frigate program. Perhaps something Canada should have thought out before we lost our AAW capability with the de-commissioning of the Iroquois class destroyers. Perhaps a re-think here in Canada seems to be appropriate as well. Could Canada acquire at least 3 Arleigh Burke Flt 111 destroyers to be built here in Canada before the CSC Type 26 Frigate build starts and perhaps build just 12 of the 9,400 tonne “Monsters”? The ABs would have at least 3 x MK 41 VLS capability with dedicated Tomahawk, SM3/SM6 missiles as well and be in service with the RCN well before the first CSC Type 26 comes off the assembly line. They would also cost less each than the CSC Frigate as well. Something to think about!

Canada could build 4 Arleigh Burke Flt 111 AAW Destroyers for $4.9 CAD for all (at 2021/2022 prices) take away. Of course this would not include the price to build here in Canada and final operational price list which would include Armament, Missiles, Bullets, Stores, Personnel etc. So say $8B CAD in service for the RCN for all 4. But still, a bargain compared to $5B CAD for one CSC Frigate bringing the CSC build requirements down to just 11 or 12 units at between $55-60B CAD (at 2021/2022 prices-using the PBOs reported price of $77B CAD). The sticking point would be acquiring the design “blue-prints” from the US and building them here in Canada if, the US would allow that (most likely they would want to build them with refits in the US only), but one could always ask . Oh, and what Canadian shipyard would get that contract!

I agree that four Flight III Arleigh Burkes would do the trick, followed by 11 CSC. They should be built in Canada to politically pass and we should eventually have an official third Yard in the NSS that is to pick-up the slack…. In order to ensure maximum commonality with the CSC and to fit our unique needs, it would need a few modification. Of course the Combat system and main propulsion plan should not change. With a good engineering team it would be feasible to modify the burke design in less than a year while the basics part of the ship could be worked on. The first change would be to replace the MK45 Gun for the Vulcano 127/64. The 25 mm MK38 gun could be replaced by the CSC’s BAE 30 mm gun but the MK38 is already fitted to the Harry Dewolf class so no sweat here. We would need to fit our brand new multirole boat (MRB) to the boat deck. The main effort would happen aft in order to fit a single CH-148 Cyclone support facilities and our very own sonar system. I could easily see the flight deck extended further forward and C-RAST fitted to it. The new single hangar would need to be moved toward the center but I don’t know the configuration of the Gas Turbine generator situated there although there is ample space to move things around back there once you go down from two to one helicopter. Also moving from two to one hangar would allow for the torpedo launcher to be installed in a fashion close to the Halifax class and using the same launcher as the CSC with the tube situated inside the ship. In order to help those change and to more easily fit our budget. I would decrease the number of MK41 launcher aft from 64 down to 16 plus the six Exls launcher removing much weight up high and maybe allowing for the installation of eight NSM launcher. In that configuration the weapon fit would closely match the one of the CSC. The Ship would carry 48 cells MK41 launcher (32 fore and 16 aft) for any combination of ESSM, SM2 and Tomahawk with the possibility of other types. It would also carry 24 SeaCeptor in the Exls launcher. Would we still fit a Phalanx? We could probably lower a bit the number of crew needed to operate the Ship but it would still require many more than the CSC. Also Operating on two LM2500 most of the time they will be using much more fuel then the CSCs. We definitely need to commission the Asterix if that was to happen!

Hello Mikael. I must agree with most of what you have said. The AB Flt 111s should be configured as closely to the CSC Type 26 as much as possible though. The AB’S would also be excellent Command ships. Crewing size may be an issue though although with Command Staff on board, perhaps not as much. The things I would change however would be: Replace the Raytheon SPY 6 V1 radar with a “beefed-up LM SPY 7 (V) (more RMA’s). This radar has already proven that it can out-perform the SPY 6 radar with longer ranges along with whatever MDA’s X Band Illumination radar will be. I would also keep the CMS 330 Combat system which already has the Aegis Baseline for CEC commonality (and BMD capability) with the CSC Frigate. Instead of the LM 2500 gas turbines, I would use 2 x RR MT 30 Gas turbines as the CSC Frigate has for increased speed (30+kts) and commonality. I can live with just one CH 148 Cyclone, however two might be better. Also increase the number of CIADS ExLS from 24 to 48 cells midships. I agree that the CSC Frigates guns should also be used on the AB’s. The NSM (Harpoon) might be increased from 8 to 16 as the Constellation class has and the CIWS could be replaced by the Dragon Fly DEW laser system port/stbd as the BAE Type 26 British version will have. As I said before, the main “sticking point” would be a built-in-Canada design (possibly Davies Shipyard) which the US would have to agree on. Other than that, your Canadian AAW/ASuW/ASW design could work well. That would be an awesome ship for Canada and could be built for the same price as 2 CSC frigates would cost!

Hi David, The problem I do see is that if we were to start modifying the combat system of the AB class to reflect the one of the CSC, this is where cost and delays would begin. It seem that part of delays surrounding the late delivery times of the CSC comes from integrating CMS 330, Aegis, SPY-7 and MDA’s illuminator radar together. Also another major cost driver would be to modify the drive train. Installing two MT30 would mean a complete new gear box and would not solve the low efficiency at low speed. The AB do use two LM2500 GT (well known to us) per shaft for a total power of 78 MW but operate like 99 percent of the time with a single GT per shat for speed up to at least 26 kts. Although the USS Truxtun is fitted with two 3.8 MW electric motor (one per gearbox) for speed up to 13 kts without the GTs. If we were to extensively modify the AB design to a Flight IV, we might as well build 15 of them but it would be as long to wait and as expensive! Too bad we are just talking here!

Hmmmm. A lot to “chew on” Mikael. The good news is that when (and if) this were to happen, most if not all of the integration for the CSC Frigate will already have been done by LM during the Design Phase so integration of all of the CSC Frigate software for the AB’s “Flt IVs” as you say, and I can live with the 4 LM 2500 GTs and the two 3.8 MW electric motors for cruising speeds would also be acceptable and not use the RR MT30 GTs. The main thing is that the AB’s can always easily keep up with the Carrier group during flight ops. But…..we are only dreaming, right?