Apollo, 6 August 2021

So, the RCN is going to put itself through the submarine acquisition wringer again. Unfortunately, there is a sad history of such programs over the last 70 years; most of which, if not all, follow the same tedious pattern from which many lessons can still be learned.

- A navy proposal based on a strategic requirement.

- Initial political scepticism and, on occasion, outright rejection.

- Extensive negotiation among politicians, bureaucrats, and the naval staff.

- Development of a politically acceptable compromise.

- A bureaucratically-driven, extended procurement process in which political concerns invariably trump operational considerations.

After the late 1970s when some well-funded special interest groups attacked the controversial nuclear submarine proposal, a cohort of new and very vocal players entered the submarine debate and, as it turned out, the larger debate on the entire defence policy process. With full war chests, the various groups systematically attacked the basic concept of Canadian submarines be they nuclear-powered, hybrid, or diesel-driven. Politically, it was a brutal and very public gauntlet to run that left deep scars.

That said, it seems that Canadian politicians have always had an aversion to submarines. There was, however, one notable exception -- the ill-fated 1987-89 nuclear submarine program which was believed to have political benefits for leverage over the Americans in the Northwest Passage. Apart from that short-lived incident, the dislike was pretty constant from the end of WWII.

Before 1945, the very modest RCN involvement in submarines during and just after the First World War and the fact that a handful of Canadians served in RN submarines during WWII were not politically sensitive issues. It was only when the RCN and RCAF needed submarines for Cold War anti-submarine training that their acquisition became politically complicated. For some reason, any type of submarine became synonymous with the German U-Boats of WWII -- that just wasn’t the Canadian way of conducting operations at sea! Eventually, de-fanged training submarines were accepted as necessary, but rather reluctantly.

So, it was under that concept that the 1954 agreement with the RN for the loan of training submarines in Halifax, the loan of USS Burrfish (HMCS Grilse) for West Coast training, and the convoluted process in 1961-3 that saw three British Oberon-class submarines acquired to replaced those on loan in Halifax. Even then, political and bureaucratic support was far from unanimous. It always seemed that some influential person had a better idea and the clout to make himself heard. The RCN’s original plan called for six American-designed modern submarines (Barbel-class) to be built in Canada but a powerful intervention and a new Defence Minister changed the plan to the three Oberons. It was just one more example where a politically motivated compromise left the RCN short on its operational requirement.

The latest submarine acquisition program for the four British Upholder-class is still a good example of how the Canadian military procurement process has become painfully slow and needlessly convoluted with more concern for political factors than the end operational product. Let me explain.

Cancelling the nuclear submarine program in 1989 for ‘financial’ reasons left the RCN with three obsolete Oberon-class submarines and no approved plan to replace them quickly. Not replacing them would not only leave the RCN without its own submarine capability but would also lead to a loss of the necessary skills to operate a submarine in the future. Against quite heavy political opposition, the RCN and its support groups waged a public education campaign arguing the reasons why submarine were a necessary capability for Canada. It took far too long to convince the political leadership to buy the British submarines and even then there was strong public opposition based largely on the old belief that ‘submarines were un-Canadian’ and, anyway, the deal was thought a poor one. The Canadian media was in the forefront of the opposition and was never convinced of their real value -- perhaps a case of ‘giving a dog a bad name before hanging it!’

In the public debate a couple of key factors were seldom, if ever, taken into account:

- The four Upholders (now the Victoria-class) met the need for quick replacement of the older submarines.

- A submarine had not been built in Canada since 1916.

- Few options for an off-shore purchase existed and those options had long wait times.

Simply, if a Canadian submarine capability was to be maintained, the Upholders were the only logical option.

All this brings me back to the future program. Here, the lessons of history point to some actions the navy planners should take early in the process. First, and probably most important, is the need to explain clearly and simply the value of modern submarines to Canada under a wide range of scenarios. Second, there should be a thorough analysis of the ability of Canadian shipyards to build a series of submarines in a timely manner. Third, a study of foreign submarines presently under construction should be done with realistic estimates of when and if a Canadian buy could be accommodated.

All that is nothing more than good staff work done by successive Naval Staffs in Ottawa since the end of WWII. Based on past experience, launching the public education campaign well ahead of any political announcement makes the subsequent steps easier. Being unable to do this nearly jeopardized the Upholder program.

One of the most difficult issues within a new submarine proposal will be the push to build them in Canada. Although preferable for nationalistic reasons, doing so runs the risk of adding extra time for both design and the necessary re-tooling of any yard selected -- or if a new yard is created for the purpose (green fielding).

At some other time and under some other political culture, the ideal solution would be for the RCN to select the best foreign design and then convince the politicians that no other logical option exists. But that really is asking too much today, isn’t it? Who ever heard of Canadian politics being logical?

6 thoughts on “Another Canadian Submarine Program: Some Useful Lessons of History”

A very interesting and thought-provoking article by the CNR Webmaster on Canadian submarine acquisition and political bungling by Canadian governments over the last 70 years. We never seem to learn from our mistakes on Naval procurements. In my opinion (IMO), once the Canadian Patrol Submarine Project (CPSP) is stood up by the RCN, one of its first mandates would be to immediately create a public document for the Canadian people explaining why Canada desperately needs to quickly proceed with a modern AIP submarine acquisition program, give them specific options and numbers required. There have never been so many options in the past as there are now. They must enlighten Canadians with the different types of modern AIP Submarines and specifically discuss submarine requirements for the future RCN submarine fleet with pros and cons of building them in Canada.

There are now several types of ocean-going AIP submarines being built by France, Germany, Spain and Japan that may “fit the bill” where once there were no options at all. These include the 12 French Barracuda Block 1A class (based on their Suffern class SSN) now being built in Australia for the RAN by the French DCNS Group; the Spanish S80 Plus class being built by Spanish company Navantia; the Soryu 29SS class with Lithium Ion Battery (LIB) technology from Japan being built by Kawasaki Heavy Industries and the German type 216 now being developed by ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems (TKMS). All have different AIP technologies, have displacements of over 4000 tons with pros and cons in all of these AIP designs. They all however, would be game changers as future Canadian submarines. The Canadian Senate recommended to the government in 2017 to swiftly acquire 12 modern AIP replacements for the beleaguered Victoria class but the government quickly rejected that recommendation. Let’s then have the Canadian people contribute to the RCN’s recommendations to the government for its final decision and quickly push forward on this!

The Australian Attack class were never designed or planned to use AIP. AIP is great if you want to only travel short distances slowly. We here in Australia (and the latest Soryu and Taigei class) decided that extra batteries were more efficient use of space than AIP.

Considering Canada has a large area of ocean to patrol like we do i assume your defence department will reach the same conclusion.

Submarines are great for many things other than the sinking of adversary ships and submarines too… not sure if your media is recognising this. SIGINT, ELINT, ESM, EW, ISR, insertion and extraction of special forces, monitoring underwater cables, patrolling with surface fleets (Canadian and allies), monitoring oversea’s disputes covertly, monitoring changes in water temperature and salinity at different depths.

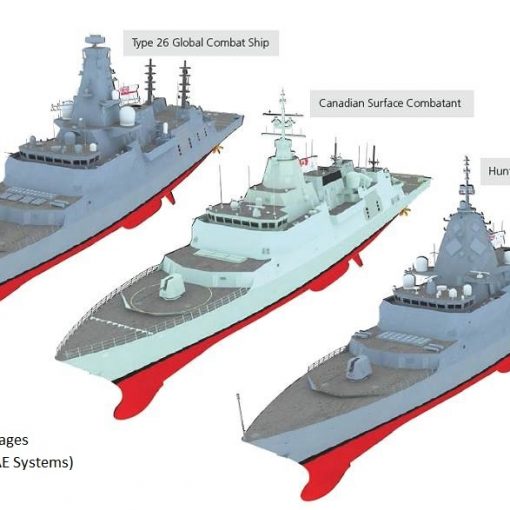

Like it or not, the fate of any submarine replacement may be tied to the Canadian Surface Combatant programme. If the costs of the latter cannot be brought under control, then it will be difficult to argue for a replacement submarine, as any estimates of the cost of a sub replacement will be highly suspect. Moreover, Canada has no sub-building skills, so there may be even more reason to doubt the feasibility of a domestic build. Yet, without the promise of jobs from domestic production, a sub replacement is highly unlikely. A Catch-22, in other words.

Canada is very tolerant of the navy having obsolescent and/or insufficient submarine capability. It is very tolerant of the politicization of defence procurement. It is intolerant of strategy. That is unlikely to change.

In light of the recent news that Australia, with the participation of the US and UK, will be ordering a fleet of eight nuclear powered submarines, would this not be a good opportunity for Canada to purchase perhaps six such subs to replace the aging Victorias? Joining this procurement could and would save the Canadian government vast sums of money, as opposed to ordering a design from scratch. The Australian acquisition is part of a regional strategy owing to the increasing aggressiveness of China, but Canada could make the same argument about Russian interest in the Arctic. I think the time has come to bite the bullet and invest in a small but effective fleet of first rate submarines capable of operating under the ice in the far north, or dispense with submarines altogether.

If (and this is a BIG IF) Canada could piggy-back on the AUKUS Pact, that would certainly help but we would need as a minimum at least 8 and possibly 10 SSNs. (3 operational for each coast with the rest in either “ramp-up/Ramp-down mode and extended maintenance periods). The bigger problem would be the extra sailors required and the infrastructure required for these boats.

I quite agree with one commenter here, that unless Canada gets on board with something like Australia, wasting time and money on these aging Victoria class subs or any similar replacement is a complete non-starter for me. The new AOPS have a very defined role that does give us some sub-Arctic presence, but limited in duration. Nuke boats would and could fill that void.