While I commend those who look into the future and contemplate interesting concepts like “influence squadrons,” counter piracy operations and humanitarian operations, I think the events of the past several days, which stem from a directive issued by the Chief of the Maritime Staff (sometimes referred to as the Commander of the Canadian navy), are of greater urgency to consider. Aside from the obvious politics of the situation, and I admire the courage of Vice-Admiral Dean McFadden in this regard, the 23 April 2010 directive issued under his signature points out the fragility of the navy at its centenary.

Essentially, the navy has two challenges: a serious shortage of trained people and a significant shortfall in operational funding. Politicians can cure the second issue; however, only the Canadian Forces (with the assistance of the government) and the people of Canada can cure the first issue. The Chief of Defence Staff can realign some funding and release some trained personnel from non-naval duties to the fleet, but such realignments will be of short term effect. The real challenge is to define the future of the navy in light of Canada’s national interests.

Our national interests have been long defined as (1) the defence of Canada, (2) the defence of North American territory, and (3) the fulfilment of our international alliances and alignments. However, it has suited every government since the Second World War, and the navy’s leaders, to employ the navy in the reverse order of these priorities. As the country works its way through the domestic and international political and economic crises of the times, there is need to revisit the priorities assigned to the navy.

If we search the history of the Canadian navy for similar circumstances, the years 1947-48 come to mind. The post-war draw down was complete, the economic times facing the country were difficult as the adjustment from a wartime economy to a peacetime footing was not yet complete. The Soviet Union and Communism were of increasing concern; however, the formation of NATO and the start of the Korean War were still in the future. Our international interests were defined by relations with the British Commonwealth, the United States and the United Nations. Defence Minister Brooke Claxton had inherited the “good workable little fleet” of his predecessor, Douglas Abbott. The navy was short of people and money but it survived. Its core capabilities were preserved and funding enabled it to sail and maintain three destroyers in the Far East during the Korean War of 1950-53. These same capabilities enabled the Cold War expansion consisting of the construction programs for new destroyers, minesweepers, reconstructed frigates and the fleet air arm.

With this history of perseverance and ingenuity, the present navy should be able to conquer the present challenges and rise again in 2017 when the Halifax-class life extension and modernization is completed. However, unless the current government fulfils the promises of new support ships, the Arctic and Offshore Patrol Vessels and provides sufficient operational funding, it will be a navy of twelve frigates, several coastal defence vessels, perhaps three submarines, and some auxiliaries. It will have the same short legs of the 1947-48 fleet, but it will lack the command facilities of the aircraft carrier, HMCS Magnificent, as the Iroquois-class destroyers will be gone. Ingenuity will be required to transform three Halifax-class ships into command frigates; however it can be done. The 2017 fleet, like the 1947-48 fleet, will be able to cruise the Caribbean Sea, the waters around the South American land mass, participate in foreign exercises, patrol Canadian coastal and, in summertime, Arctic waters. However, the concept of a fully self-sustaining Canadian task force will be at risk, if not lost altogether.

The key to a capable navy is a consistent supply of trained, dedicated, innovative officers and non-commissioned personnel. Without such people there is no navy and therefore no need for ships or submarines. Money is necessary to make the navy function but it is the people that are the real asset of the fleet. Therefore, the knowledge, skills, and expertise of naval personnel must be maintained and increased. This is the true core function of the existing navy. It was the core activity of the 1947-48 navy.

In 1947-48 the carrier was the central operational ship and it was usually supported by two Tribal-class destroyers from the east coast navy. In addition there was a training group usually comprised of a destroyer and two River-class frigates. The west coast navy had a destroyer flotilla and a training group as well. The cruiser, HMCS Ontario, was the capital ship but it was assigned to officer training duties. The minesweepers of the day, principally Algerine-class ships trained the reserves on both coasts and the Great Lakes, along with a number of Fairmile-class patrol vessels. The entire fleet was essentially still in Second World War configurations. These were the ships that trained and employed the crews that enabled the navy to go to war in Korea. They provided the foundation for the Cold War navy.

The current naval leaders, at all rank levels, must look for practical solutions to overcome current challenges. The solutions may require the elimination of some ‘near sacred’ ships and desires. Sinking huge sums into forty year old supply ships and destroyers to gain another five or seven years of service may not be practical or sensible investments when practical alternatives are available. The need for resources for the fourth submarine when it is proving difficult to maintain just one of the remaining three subs operational must be reviewed. Transfer of some of the coastal defence vessels to a Caribbean navy or coast guard may be of more political, diplomatic, and institutional value than their underutilization in our fleet, particularly if the Arctic and Offshore Patrol Vessels materialize.

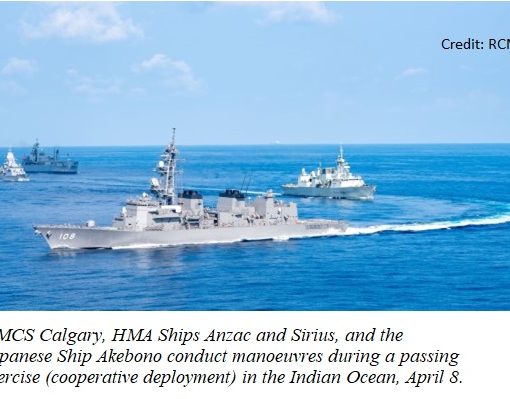

To maintain a competent navy it is critical that the fleet be deployable as a Canadian task group. This means that there must be experienced officers and non-commissioned members who can command the formation, use its combat resources effectively in either national or alliance operations, and sustain the force using afloat logistic support that is integral to the task group. If such support must be found in a double hulled commercial tanker taken up from trade and suitably modified, such as HMAS Sirius, so be it. It is in Canada’s national interest for the navy to be able to deploy in home waters and abroad as a self-contained force.

If Canadians, of all walks of life, can encourage our federal politicians and the leaders of our navy to be creative, innovative and practical, then the Canadian Navy will be Ready Aye Ready.