*Moderator's Note: This commentary was published in the June issue of “In Focus.” The commentary is reprinted here with the permission of the author. My thanks to CFPS Research Fellow Dr. Stan Weeks for bringing this article to my attention.

“The Sinking of ROKS Cheonan” by Brett Witthoeft

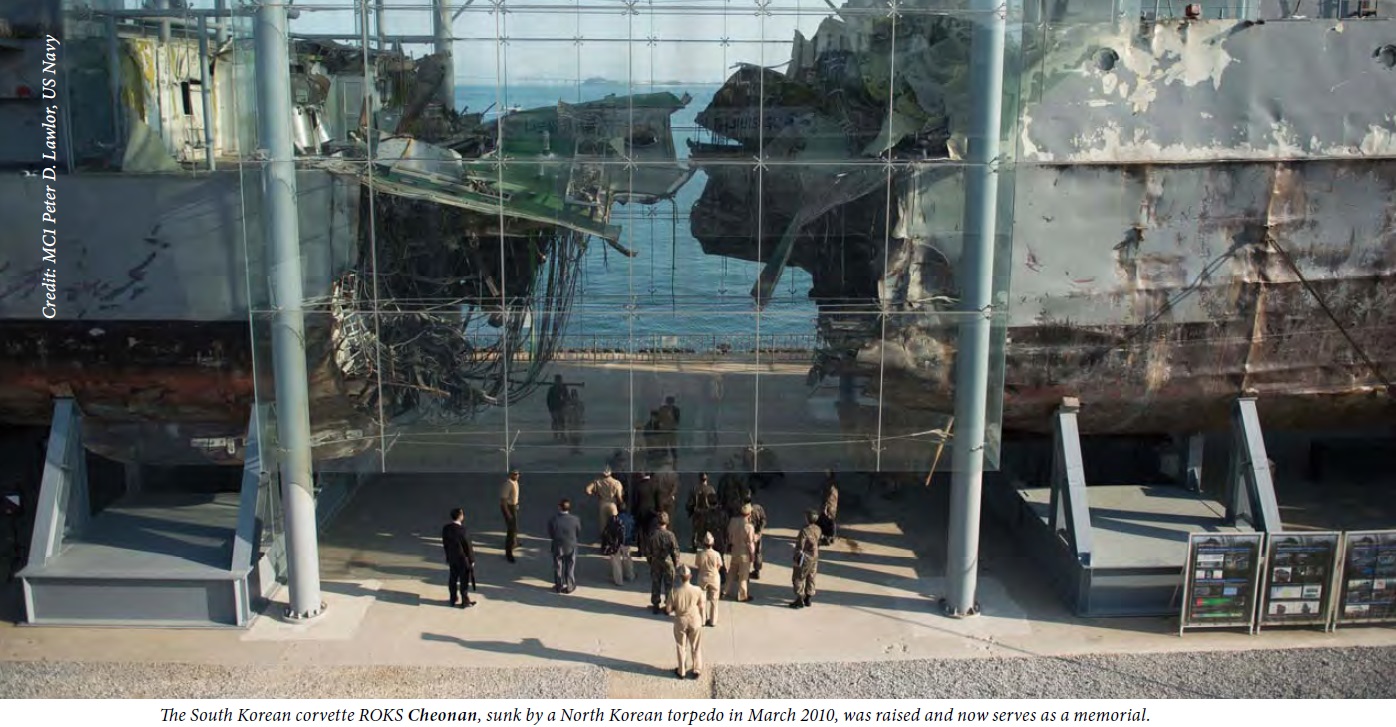

On 26 March 2010, an explosion occurred near the stern of ROKS Cheonan, a South Korean Pohang-class corvette, approximately one nautical mile southwest of Baengnyeong Island in the Yellow Sea, west of the Northern Limiting Line (NLL), the de facto maritime boundary dividing the Koreas. The explosion, which came without warning, caused Cheonan to break in half and sink in five minutes, killing 46 South Korean sailors.

Following the incident, Seoul remained remarkably composed, and deferred a reaction until a multinational investigative group released its findings, even as rumours swirled, most involving North Korean culpability. When the Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group’s (JIG) report eventually was released on 20 May, it found that Cheonan’s sinking was far from accidental, and that “[t]he evidence points overwhelmingly to the conclusion that the torpedo [that sank Cheonan] was fired by a North Korean submarine.” Since then, South Korea, the U.S., and Japan have undertaken punitive measures against the North while putting pressure on China to do the same – to which Beijing has so far demurred – even as Pyongyang has severed ties with the South and threatened all-out war.

Even with the JIG’s report indicating without ambivalence that North Korea was responsible for Cheonan’s sinking and the deaths of the 46 of her crew, many questions over the incident remain. Why did North Korea attack Cheonan? What will be various countries – especially China’s – reaction to the incident? And what is the way forward for South Korea and its allies?

The Investigation

The JIG team, which was composed of investigators from the US, UK, Sweden and Australia in order to give it impartiality and international credibility, concluded that Cheonan was sunk by a North Korean torpedo, most likely fired by a North Korean midget submarine with the intent to severely damage or sink the corvette. On the first point, a dredging ship that worked at the sinking site found on 15 May the remnants of a torpedo, including propeller blades, motor, and steering section. The recovered pieces match exactly those of the CHT-02D torpedo, which North Korea markets for export, and the markings on the propulsion section read “No. 1” in Hangul, which is consistent with a North Korean torpedo obtained in 2003. Early on in the investigation, the South Korean Defense Ministry revealed that traces of RDX identical to that in the 2003 torpedo was found on the wreckage of Cheonan. RDX is most used in North Korean torpedoes, and since Russia and China label their torpedoes in their own language, it was fair to conclude that the torpedo fragments were of North Korean origin.

On the second point – that the torpedo was fired by a North Korean midget submarine – the Multinational Combined Intelligence Task Force, comprised of Canadians, Americans, Britons, and Australians, along with the Republic of Korea Navy (ROKN) noted that at least four submarines and a support ship – the latter was dispatched to provide sonar cover for the subs – departed the Cape Bipagot naval base in South Hwanghae province – North Korea’s primary submarine base in the Yellow Sea – two to three days prior to the attack, and that they returned to base two to three days following the incident. The Cape Bipagot facility is known to house several Sang-O-class medium-size and Yeon-O-class midget submarines – both types are capable of firing the torpedo that sank Cheonan, and are optimised for special operations. Furthermore, according to the task force, “all submarines from neighbouring countries were either in or near their respective home bases at the time of the incident.” Given that a North Korean torpedo was recovered, that North Korean vessels were likely in the area at the time, and that other instigators can be ruled out, it is reasonable to conclude that a North Korean boat fired the torpedo, most likely a Yeon-O-class midget submarine.

The final matter is the torpedo having been fired with the intent of critically damaging or sinking Cheonan. The JIG group found that the torpedo did not physically strike Cheonan, but exploded at a depth of six to nine metres and three metres to the left of Cheonan’s engine room. The result of this underwater explosion was a powerful upward-moving bubble shockwave that caused Cheonan’s keel to bend violently and split almost-evenly. This explanation is strengthened by the fact that heat damage was not found on recovered parts of Cheonan, which would have indicated a direct torpedo strike. Moreover, damage to bodies from the wreck displayed fractures and lacerations, which are consistent with shockwave injuries, and a seismic event consistent with a shockwave was triangulated to the area by South Korean seismic monitoring stations. Such a precise explosion is highly unlikely to be an accident, and the torpedo was almost certainly fired with the intent to create the bubble shockwave, which would have at least severely damaged Cheonan. Thus, the investigators deemed that it was extremely likely North Korea was responsible for Cheonan’s sinking.

The Aftermath

Armed with the JIG’s report, South Korean President Lee Myung-bak announced in a nationally-televised speech on 24 May that his government would take several steps in response to Pyongyang’s provocation, including: suspending trade and humanitarian ties with the North; denying North Korean ships access to South Korean sea lanes; bringing the matter before the UN Security Council to seek punitive action, and; resuming “psychological warfare” against the North, including the broadcasting of anti-Northern propaganda across the border. South Korea accounts for roughly one-third of overall trade with the North (China is North Korea’s greatest trading partner by far) with goods like rice, seafood, fertiliser, manufacturing equipment and computers flowing from the South to the North. The embargo is predicted to cost Pyongyang USD $200 million annually, a substantial sum when the country’s GDP is estimated at a mere $40 billion. The denial of South Korean waters to North Korean vessels will have a magnifying effect as well, since it will become more difficult, time-consuming, and expensive to ship goods to the North as cargo ships take more circuitous routes or goods are shipped over land.

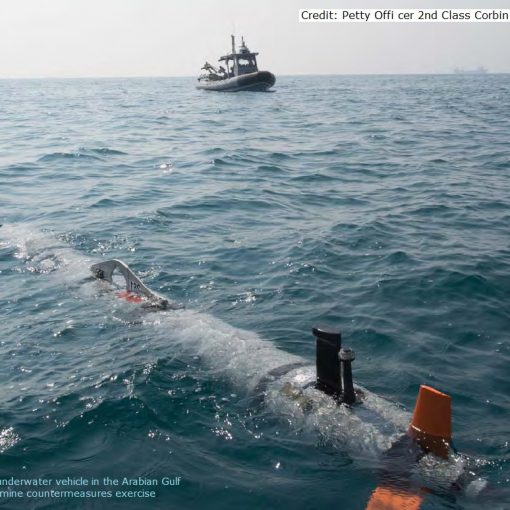

South Korea also had a military response. On 27 May, the ROKN held a live-fire anti-submarine exercise in the Yellow Sea with 10 warships, including a destroyer, approximately 150 kilometres south of the NLL. This action was reinforced by an announcement that the ROKN will conduct bilateral anti-submarine and maritime interdiction exercises under the auspices of the Proliferation Security Initiative with the US Navy (USN). The first exercise is to take place near the NLL 8–11 June, including the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS George Washington, an ‘Aegis’ ballistic missile defence-equipped destroyer and a nuclear submarine from the USN, and a destroyer, a submarine, and F-15K fighter jets from South Korea.

After denying responsibility, calling the JIG’s report false, and promising “all-out war” in the event of a South Korean military reaction, Pyongyang responded by expelling South Koreans from the Kaesong joint industrial park – a significant source of revenue for the North – and severed communications with Seoul, including a maritime hotline established to prevent accidental maritime clashes. Pyongyang also demanded that its own investigators be given access to Cheonan evidence, which was rejected by Seoul.

According to South Korean intelligence, rumours that the North had taken revenge on the South circulated heavily, to the point where they were addressed in Korean Workers’ Party (KWP) meetings, though Cheonan was not specifically identified. At the same time, Pyongyang dispatched lobbyists to promote the North Korean perspective, selectively mixing information and disinformation to suggest that North Korea was not at fault for the attack – Kim Myong-chol, a long-time friend of Kim Jong-il, argued in Tokyo that Cheonan was likely sunk by a USN torpedo – and that quietly appeasing Pyongyang was the best course of action.

International Reaction

Condemnation of the North has been uniform across the globe, while South Korean allies, such as the US and Canada, have expressed solidarity with Seoul and increased trade sanctions against the North. Even Japan has levied new sanctions against the North, and has gone further by passing a law permitting the Japan Coast Guard to inspect suspect North Korean cargo (with the caveats that permission be granted by the country under whose flag the ship is registered and the ship’s captain).

China, North Korea’s closest ally, called Cheonan’s sinking “unfortunate,” and has so far attempted to downplay the incident and avoid becoming involved in punitive measures. On the weekend, before Seoul’s announced the severance of links with the North, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (along with a 200-strong American delegation travelling for the annual US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue) discussed the Cheonan incident with her Chinese counterparts. Clinton specifically spoke with Dai Bingguo, one of China’s highest-ranking diplomats, about the Cheonan affair, but little appears to have come of the meeting.

The leaders of South Korea, Japan, and China met on Jeju Island, South Korea, on 31 May for their third trilateral summit since 2008, and for the first time, regional security was discussed at the meeting. President Lee, then-Japanese Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, and Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao agreed to uphold the conclusions of the JIG report, but Wen did not support Lee’s firm stance toward North Korea and instead favoured easing the fallout and the lowering of regional tensions.

Analysis

By far the greatest question to emerge from Cheonan’s sinking is why North Korea did it. One explanation is that the North was retaliating against the South for the 10 November 2009 skirmish between the Korean navies near the NLL off Daecheong Island, which saw a North Korean patrol boat seriously damaged and one North Korean sailor killed. Kim Jong-il and his third son and heir apparent, Kim Jong-un, reportedly visited naval command in late December 2009 and ordered the November clash be avenged, which may have been the impetus for the attack on Cheonan. There have also been numerous reports that the succession of Kim Jong-il by Kim Jong-un is tenuous, and an international provocation is standard fare for the elder Kim in troubling times.

Another potential reason for the attack is rich crab fishing grounds around the NLL. The crab fishing season typically runs from June to September, and the two Koreas clashed in June 1999 and June 2002, and in November 2004 and November 2009 over the crab-rich waters. The crab trade is a lucrative source of income for North Korea, with Hwang Jang-yop, North Korea’s highest-ranking defector, estimating USD $100 million annually from catches. Since only the navy and military families can fish for crab during the prime season, it acts as an important loyalty-generating mechanism between Kim and the navy. Although the military is favoured in food rationing, crab is likely a very important source of protein in a country where the estimated daily caloric intake is around 1,000 calories of carbohydrates.

However, when the ROKN and USN exercise near the fishing grounds of the NLL, North Korea will have few opportunities to poach from South Korean waters. Furthermore, given the timing and scope of the first joint drill, the season may be disrupted, thereby diminishing North Korea’s catch this year. If crab fishing was a motive for the North, it will likely have backfired because of the USN-ROKN exercises.

Adding to the need for protein and revenue from crab fishing is the fact that North Korea “revalued” its currency in November 2009, purportedly to crack down on burgeoning private markets. The currency revaluation failed dismally, with the price of rice increasing 70-fold, sparking riots over food shortages, high inflation, and decimated savings. Although elites were reportedly warned of the revaluation, it is believed that many officials were seriously affected. This spurred a backlash against Kim Jong-il, one that Dear Leader could ill-afford in view of reports of his poor health and Kim Jong-un’s succession seemingly still tenuous. The revaluation also made currency exchanges difficult, so black market trade along the Chinese border – which is conducted in yuan or Western notes – would have been curtailed as Chinese merchants recoiled from the uncertainty, further fuelling popular unrest.

No matter Pyongyang’s intent, the sinking of Cheonan has significantly restricted North Korea’s already few trade options. The primary variable at this point is China, and whether it will support its Korean ally. Kim Jong-il met with Chinese officials, including Premier Wen and President Hu, in China in early May. Kim reportedly told Hu that the North was not responsible for the attack, a declaration that was later repeated in a briefing on Kim’s visit to South Korea on 7 May, although Kim was not identified during the South Korean briefing.

Kim’s lie is no doubt galling to Beijing and has caused considerable embarrassment for the Chinese, who were forced to take Kim at face value. Despite this, Beijing has minimised the Cheonan attack – though it has stopped short of supporting Pyongyang – and its actions to date suggest it will resist further sanctions on the North. The burden on China to support its ally will grow measurably because of other countries’ sanctions on the North, but Beijing will likely carry this crucible to avoid the North’s collapse, which would likely result in millions of North Korean refugees crossing the border into Liaoning and Jilin, two of the poorest and least-developed provinces in China and ill-equipped to deal with desperate North Koreans.

On a more positive note, Tokyo’s cooperation with Seoul is promising. Although both Japan and South Korea share the common thread of close military alliances with the US, they have been unable or unwilling to foster bilateral ties, mainly due to historical disputes, especially those arising from Japan’s WWII conduct. The Cheonan incident offers the opportunity for Tokyo and Seoul to cooperate on security issues – with or without the US. This is particularly the case in the maritime realm, where both countries’ navies can share information and best practices on anti-submarine warfare, with respect to North Korean submarines.

Finally, the Cheonan sinking has brought the US and South Korea closer together. Seoul announced on 31 May that it will review its defence policy, and it is possible that the April 2012 transfer of command of ROK and American forces in South Korea to South Korea may be suspended. Furthermore, high-ranking South Korean officials are calling for the development of greater strategic offensive weapons to deter the North, which President Lee initially advocated in 2008 when he took office. Washington is already a prime supplier of weapons to South Korea, and if Seoul decides to acquire strategic weapons, the US is likely to be its first source.

In sum, although there are precedents for North Korean attacks on the South – perhaps over crab fishing – this incident has gone much further than previous incidents and will likely prove more harmful than beneficial for North Korea in the short- and medium-term, though it may achieve the goal of smoothing Kim Jong-un’s succession. In the long-term, Pyongyang’s relationship with Beijing has been marred, though China will likely continue at least material support to its erratic ally for fear of the country imploding. Though Beijing’s reaction will, no doubt, continue to be unsurprising, its actions in regards to the Cheonan sinking in the coming weeks will reveal much about the likely future of the China-North Korea relationship.